by Debbie Allyn

Historical records suggest that the area surrounding Lake Minnetonka, located approximately twenty miles west of Minneapolis/St. Paul, was considered “holy ground” to the local Dakota natives. To date, local historians have gone to great lengths to record the early history of white settlers in the area. Whether intentional or unintentional, early Dakota history resides in first-hand accounts of the relationship between the settlers and the natives. These written records provide a primary source of information that allows researchers access to the spiritual meaning of Lake Minnetonka within the indigenous culture. While many conflicts occurred across the state of Minnesota during the Dakota Uprising, the area directly surrounding Lake Minnetonka was spared from battles. This was due to the spiritual significance of the area by the indigenous tribes that called this lake their home.

Archaeological remnants prove American Indian habitation of the boreal forest to approximately 11,000 years ago, with burial sites dated 2,500 years. The numerous burial sites of Lake Minnetonka rank third in the state of Minnesota, preceded only by Lake Mille Lacs to the north and the Red Wing Valley to the south (Mugford 1993). As primarily forest dwelling natives, the only form of transportation available was by foot or canoe. Lacking any direct access from the city, the area remained a Dakota secret until 1852. It was the extensive water system flowing from St. Anthony Falls by way of Minnehaha Creek to Lake Minnetonka that eventually led the white man to the Dakota Territory. Dubbed “lac gros grand bois”, or “big lake in the big woods” by French traders of the 1670s, the area was rich with game and contained an abundant fish population.

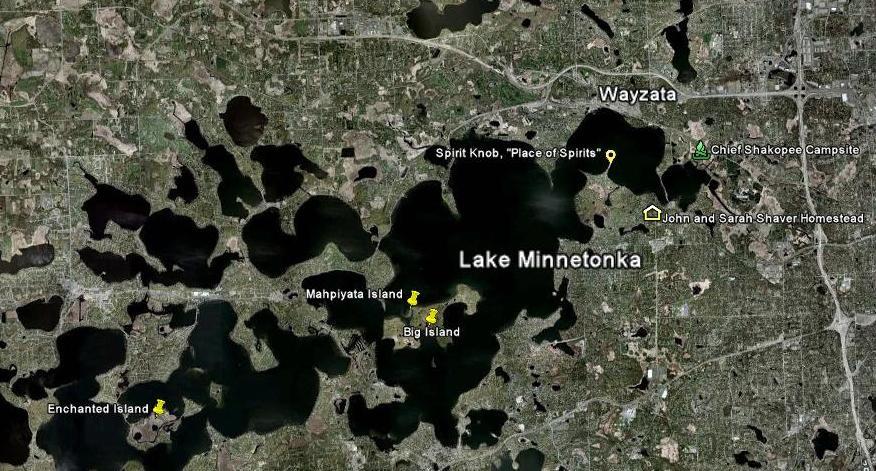

Minnesota was declared a territory in 1849, and nine-tenths of it remained occupied by various Indian tribes whose culture lacked a concept for land ownership. Translated, man could not own the land; he only had the right to “occupy” it. This ideology was greatly contrasted by white settlers, having mainly come from Europe where complete ownership of the land, particularly by the wealthy and powerful, was the norm. As if sensing the inevitable, the Dakota went to great lengths to keep the Lake “secret” from the white man. This lake includes several substantially sized islands that have a long-standing history of spiritual and cultural meaning within the Indian culture. Especially recognized is the bluff of Spirit Knob, in conjunction with the islands of Mahpiyata, Big Island, and Enchanted, all of which figure prominently in Lake Minnetonka history.

Known to the Indians as Point Wakon (Place of Spirits), Spirit Knob was the highest point of the lake. Evidence of ritual practice is documented in several first-hand accounts that refer to the notable landmark known as Spirit Knob to the white settlers. The beautiful island was recognized by Indian Tribes to be the home of Manitou, the Spirit they believed ruled the waters of Lake Minnetonka. With its uniquely shaped bluff, one personal account describes the point as “picturesque as a bit of Japanese mountain landscape” (Richards 1957).

Figure 1, Lake Minnetonka (Image from Google Maps 2010, Landmarks from Picturesque Minnetonka 1976) [Map correction: Spirit Knob is actually located on the nearest peninsula directly southeast of the pictured pin.]

At the edge of the bluff sat a great cedar tree, whose projecting roots and twisted branches signified the strength, power, and age of the spirit, which was believed to control the waves and the winds. Located near the cedar tree was a large stone painted red with yellow markings. A man, referred to only as Dr. S of St. Louis, was determined to discover its meaning and sought out an unnamed Sioux Chief who shared the history of the stone as it pertained to the indigenous people. The stone, he explained, had been in the same spot since his people had arrived in the area many generations ago, and had become an altar for the offerings of scalps obtained in battle. Historical records indicate that, for many years after leaving the area, small tribes of braves (Indian soldiers) and squaws (Indian women) returned yearly to pay tribute to their Spirit, Manitou. Additional ceremonial items, such as significant markings on the trees and ruins of less permanent altars, further support the location as a holy ground (Meyer 1980).

The small island of Mahpiyata is named in accordance to the Legend of Mahpiyata. The daughter of Chief Wakanyeya, Mahpiyata was said to be the most adorned maiden within her father’s tribe. Conflict between the Ojibwe and the mighty Dakota had continued for generations, when an Ojibwe warrior party came down from the north to engage in warfare with their sworn enemy. Early detection of the impending ambush led Chief Wakanyeya to send a band of warriors to destroy the intruders. Mahpiyata begged her father to let her join the campaign against the Ojibwe, and he consented with her promise that she stay out of sight and observe the battle from a safe distance.

As the battle grew difficult for her people, she came out of hiding to support the young braves with words of encouragement. Admiring her bravery and courage to come forth, while captured by her beauty, the Ojibwe war leader, Tayanwada, ordered her to be kept unharmed and claimed her as his war prize. After living among the Ojibwe for about ten years, Mahpiyata married her captor Tayanwada, who loved her dearly and had since become the chief.

After many years together, Mahpiyata eventually persuaded her husband to negotiate peace between the long feuding tribes, Ojibwe and Dakota. As peace between the nations occurred, a great celebration ensued on Big Island that is said to have lasted for several days. Many years after their success to unite the two Indian nations, Mahpiyata and Tayanwada were laid to rest, side by side, a Dakota and an Ojibwe on the north end of the Island: “With the red wand they passed the bad spirits, with the blue wand they passed the tempting spirits, with the white wand they passed into the beginning of a higher life. Thus ends the legend of Mahpiyata” (Richards 1957). The burial site of Mahpiyata and Tayanwada in itself is supportive to the Island and its sacred meaning to the Dakota, while the legend surrounding the pair is indicative of the oral history of the area.

Enchanted Island, referred to by the Indians as Wa-kon-wi-ta or “Great Spirit Island,” is historically accepted as the chosen location of worship and incantation of medicine men from several tribes. Legend surrounding the Island claims it to have been the home of a squaw named Manitoucha. She was the daughter of a great medicine man who had long since passed by the time the first settlers arrived. Anonymous hand-written notes discovered by the Wayzata Historical Society provide the following comments regarding Enchanted Island:

Sacred to the peace loving God, Great Manitou (promise of land), the island is described as the “most pleasantest place on earth.” Fruit hanging from the trees, berries on the bushes, fat deer roaming, and populated with birds, the island is as beautiful as a lovely woman. No bloodshed should ever violate the sanctity of this land.

Similarity in the names of the medicine man’s daughter and the Great Manitou may be offered as support of the local legend. Independent sources have mentioned Manitoucha to be the foster mother of Little Six, otherwise known as Chief Shakopee. While no written records have provided official documentation, the legend persists in local history.

Despite the tribes’ attempt to keep this sacred expanse hidden, white settlers eventually located the area. During the spring and summer of 1852, the first squatters arrived on the southeast shores of Lake Minnetonka. It is generally accepted by local historians that “the pioneer of Minnetonka” was Simon Stevens, who occupied a 160-acre claim near the lake outlet at an area known as Minnetonka Mills. Arriving by “mud wagon” on November 8, 1852, John, Sarah, and their son Eldridge Shaver, became the first white family to settle in the area. The date, recorded in granite on Sarah’s headstone is part of the epitaph that reads “the pioneer woman of Minnetonka,” located at Groveland Cemetery (Richards 1957).

Sarah permanently distinguished herself within the area when, on August 12, 1853, she became not only the first mother to give birth in the newly formed colony, but also the first mother, red or white, to give birth to twins. This was incomprehensible to the Sioux, as twins were completely unknown in their culture. Word spread quickly of the birth, and as recorded in several historical resources, the Indians came from miles away to see the white woman who gave birth to the “two papooses.” Noted in the memoirs of the late Bayard Shaver, the Shaver family were unconcerned when, disbelieving the stories of such a birth, “a large delegation of squaws, headed by a medicine man came” to see the babies for themselves. Sharing his family’s account of his and his brother’s infamous arrival into the world, Shaver wrote in his memoir, “At last the medicine man who could speak a few words of English…pointing to my brother, who was fat and rosy, exclaimed: ‘Tonka papoose! Tonka papoose!’ Then turning to me, thin and cadaverous, murmured in a mournful manner: ‘Poor, poor little papoose, he got none mammy!’”

The birth of Bayard and Bernard Shaver and its effect on the locals was significant in supporting the peaceful relationship that existed among the local Indians and white settlers of Lake Minnetonka. Through personal recollections, it remains apparent that the settlers never considered themselves in danger. At the onset of the Dakota Uprising, many settlers outside the Lake area fled to the safety of Fort Snelling. However, lake settlers, having had first-hand experience with the Dakota natives’ spiritual meaning of Lake Minnetonka, never felt the urge to flee.

According to a website about the history of Lake Minnetonka compiled by Jim Gilbert, in 1851, the Treaty of Mendota was established, transferring two million acres of Indian land, including Lake Minnetonka, to the U.S. government. Dakota leader Hockakaduta asked that the area around Lake Minnetonka remain Indian land. However, the U.S. government ultimately denied the request, which resulted in most of the Chiefs refusing to sign. Despite the lack of signatures, the Treaty was enacted on August 5, 1851.

Following the signing of the Traverse de Sioux and Mendota treaties in 1851, both the upper and lower bands of Sioux became resentful toward the white man’s promises of supplies and funding. Fur traders began giving credit to the Indians “as a favor to the Indians” to avoid starvation. When funds were finally dispersed, they went directly to the fur trading agents, who cheated the Indians by way of over inflated costs and extremely high interest. The economic concept of currency as a tool for trade was still a very new concept for the Indians, who had relied on trade via material objects for generations. Feeling cheated, not only had they lost all rights to the land that had sustained them for many generations, but they now faced the difficulty of survival within a culture that excluded their way of life.

With the intent to adapt the natives to the ways of the white man, several attempts were made to instigate farming as the new, “preferred” tool as a means of economic support for the Indians. It stands to reason, since the white man had every intention of taking control over the age-old hunting grounds that had provided the Indians a way of life for hundreds of years. Justification of progress could be supported by offering the attempts of civilizing the natives through farming. Finding it difficult to conform to these new methods, many Indians continued to hunt for survival. Unfortunately, the white man saw this as an “intrusion” of the property he now owned.

The resentment exploded on August 17, 1862 when Indian hunters turned on a group of white settlers near Acton, Minnesota. A band of four hunters from the Rice Creek Village known as Brown Wing, Breaking Up, Killing Ghost, and Runs Against Something When Crawling had been on a hunting expedition and were heading west toward their village when they came upon the nest of a hen. The hen’s nest lay on the edge of the Robinson Jones homestead, and one of the band members warned another that the eggs belonged to the white man. The young warrior resented the warning and as his anger began to rise he pronounced, “You are afraid to take even an egg from him even though you are half starved” (Bergmann 1957). Confronted with a lack of bravery while feeling the need to prove himself, the young man took action that resulted in the death of five innocent victims.

The killing of the young band of hunters set off a chain of events that would eventually lead to an extermination of Native Americans and their culture, forcing them into exile in a world that had no place for Native customs and traditions. It came as a surprise to both Indians and whites when organized attacks occurred at Fort Ridgeley on August 20 and 23, and in New Ulm on August 19 and 23. Feeling the threat of warfare, settlers, along with a few Indian farmers who had attempted to conform to the white man’s ways, fled to the east for safety.

Chronology of the Dakota Uprising

August 17, 1862 Murder of five settlers at Acton in Meeker County

August 18, 1862 Attacks on Upper and Lower Sioux Agencies and the ambush at Redwood Ferry

August 19, 1862 First attack on New Ulm

August 20, 1862 First attack on Fort Ridgeley; attacks on the Lake Shetek and West Lake Settlements

August 22, 1862 Main attack on Fort Ridgely

August 23, 1862 Second attack on New Ulm

September 2, 1862 Battle of Birch Coulee

September 3, 1862 Skirmish at Acton and attack on Fort Abercrombie

September 4, 1862 Attacks on Forest City and Hutchinson

September 6, 1862 Second attack on Fort Abercrombie

September 23, 1862 Battle of Wood Lake. The Dakota are camped in Yellow Medicine County when attacked by Sibley’s army killing Chief Mankato. Little Crow retreats up the Red River with some of his people

September 26, 1862 Surrender of captives at Camp Release

September 28, 1862 Military commission appointed to try Indians who participated in the uprising

December 26, 1862 Chief Shakopee is one of thirty-eight Sioux executed at Mankato

Despite awareness of the uprising, peace among the Indians and the settlers continued in the Lake Minnetonka area. Chief Shakopee and his tribe returned from buffalo hunting in the Midwestern plains every winter to camp on the northeast side of the lake. Chief Shakopee was popular and well respected among the white settlers. He made the ultimate sacrifice to his native people when, after losing a war he argued against waging, he, along with thirty-seven others, suffered the fate of death by hanging on December 26, 1862 in Mankato, Minnesota. Upon his death, Shakopee’s body was sent to Philadelphia for dissection. His bones made their way back to Minnesota and were displayed in a museum where they were eventually discovered by his great-granddaughter in the mid-1970s; after many years he was finally returned to the family.

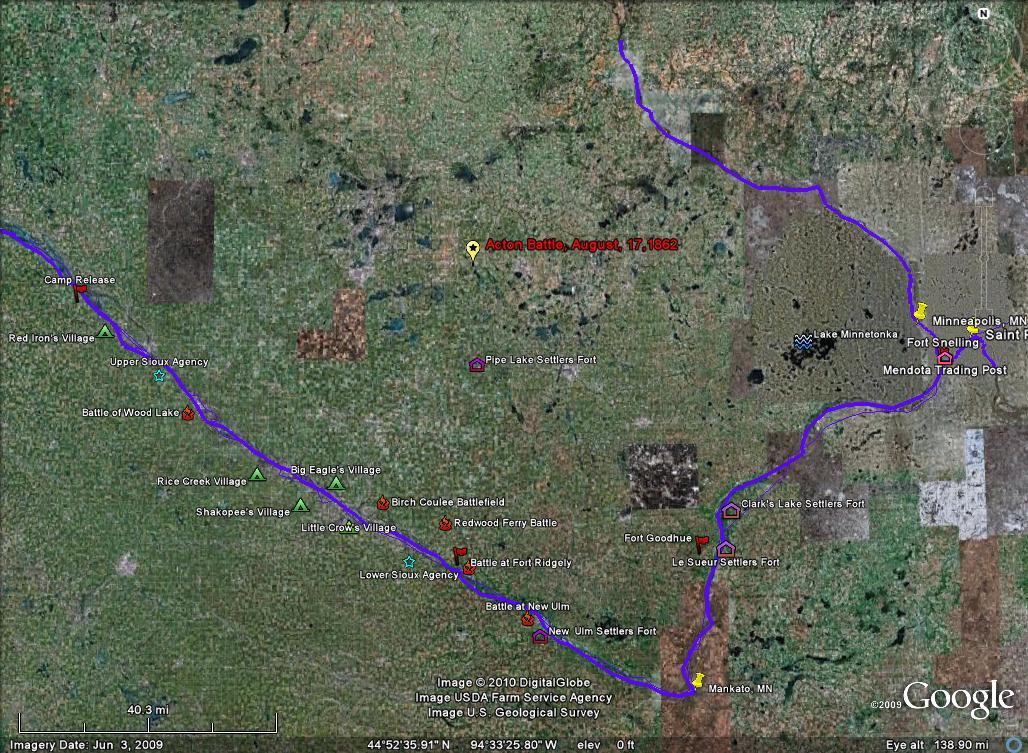

Figure 3 depicts a map indicating battle sites during the uprising of 1852. This furthers the support of the claim that Lake Minnetonka was considered holy ground to the indigenous people.

Figure 3, Minnesota River Valley (Information from Google Maps 2010, Landmarks from Bakeman and Richardson 2008)

Following a battle plan along the Minnesota River secured by several military forts, it appears that this area was tactically ineffective compared to the northern and eastern routes. The area, while populated, remained vulnerable to attack, as the single nearest military fort was approximately thirty miles to the east.

When the Dakota lost rights to their land, they lost the sacred grounds, which had been central to their culture for many generations. It is this spiritual attachment to Lake Minnetonka that supports the claim that the area saw no violence during the uprising and relations remained peaceful between the white settlers and the Indians. As a country based on the right to religious freedom for all, it is interesting that the white settlers did not think twice before forcing the Indians west. It is truly a shame they could not gather up the holy ground with the rest of their possessions. However, had that been possible, it is likely they would have chosen not to, for no man can own the land—he can only borrow from it.

References

Anonymous hand written notes. Date unknown. Wayzata Historical Society.

Bakeman, Mary Hawker and Antona M. Richardson. 2008. Trails of Tears: Minnesota’s Dakota Indian Exile Begins. Roseville: Prairie Echoes press.

Carley, Kenneth. 1976. The Sioux Uprising of 1862. St. Paul, Minnesota Historical Society. Second edition.

Excelsior-Lake Minnetonka Historical Society. 1976. Picturesque Minnetonka. May 1976. S.E. Ellis 1901-1912.

Gilbert, Jim. “A Brief History of Lake Minnetonka.” Lake Access — Lake Minnetonka History. http://www.lakeaccess.org/historical.html.

Google Maps. 2010. “Lake Minnetonka.” Accessed April 1.

Google Maps. 2010. “Minnesota River Valley.” Accessed April 1.

Meyer, Ellen Wilson. 1980. Happenings around Wayzata. Excelsior, MN. Tonka Printing Co.

Mugford, John. 1993. “For a time, Lake Minnetonka was a Dakota secret.” Minnetonka Sun Sailor Newspaper. April 7.

Richards, Bergmann. 1957. The Early Background of Minnetonka Beach. Minneapolis, Minnesota: The Hennepin County Historical Society.

Shaver, Bayard. Old Picket Fences. Personal memoirs. Wayzata Historical Society.