by Brittany Nelson

1980 marked the beginning of a transitional time for female representation and acceptance of feminist ideas in the United States and North Hennepin Community College (NHCC). 1980 was an election year, which helped to bring women’s rights, and especially the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), into the national conversation. Although the ERA failed to be ratified, this conversation affected the ways that women lived their lives. At North Hennepin Community College, national discussion of the ERA translated into more female representation in the arts and literary magazine Under Construction. The increase in female representation comprised of an increase in female writers contributing to the magazine, as well as an increase in stories with feminist themes.

Before exploring the ways that the ERA affected female representation in Under Construction, it is important to understand the arguments present on both sides of the debate surrounding the ERA during the late 1970s through the early 1980s. It is also important to note that the debate surrounding the ERA was heavily influenced by both pro and anti-feminist ideologies. The ERA itself states that, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex” (“The Equal Rights Amendment” n.d.). The original goal of the ERA was to ensure that women could not be excluded from laws passed by the federal or state governments that granted legal rights (Weber 2008). Feminist groups hoped that passage of the ERA would, among other things, provide more opportunities for women in the workplace by allowing women legal recourse in the face of gender discrimination, as well as providing strong legal protection for reproductive rights (Weber 2008).

During the 1970s, Phyllis Schlafly became one of the biggest opponents to the ERA (Weber 2008). Her arguments against the ERA appealed to women who were happy to adhere to traditional female gender roles by staying home to raise children while their husbands worked to earn the family income, and felt that their way of life was being ridiculed by feminists who overemphasized the importance of women in the workplace (Weber 2008). Opponents of the ERA claimed that the amendment would only benefit working women by nullifying laws that required a husband to provide for his family (Weber 2008). Another concern was that passage of the ERA would eliminate the requirement that the military draft only accept men (Weber 2008). This not only concerned opponents of the ERA and proponents of traditional gender roles, but also women that held any beliefs about feminism and were afraid of facing combat. Finally, opponents of the ERA warned that its passage would legalize gay marriage and abortion, which they claimed would threaten the traditional structure of the American family (Weber 2008).

Now that the arguments on both sides of the ERA debate have been established, it is important to look at the ERA’s history. On March 22, 1972, the ERA had been passed by both the House and Senate. The next step was to get 38 states to ratify the ERA, but by 1978, only 35 states had done so (“The Equal Rights Amendment” n.d.). Congress had originally placed a seven year limit to pass the amendment, which would have meant that 1979 was the year it would expire (“The Equal Rights Amendment” n.d.). However, in 1978 Congress decided to extend that deadline to June 30, 1982 (“The Equal Rights Amendment” n.d.). This meant that women’s rights and the ERA were very much a part of the national discussion as the 1980 election rolled around.

By reading the student produced newspaper the North Star, it is clear that the outcome of the 1980 election would greatly affect the fate of the ERA. An article from October 30, 1980 discusses a lecture given by Gloria Steinem, a then prominent leader of the feminist movement. During her lecture, she says that if Ronald Reagan won the election, “Women’s rights will suffer enormously and the ERA will probably not be passed (qtd. From Sievert 1980).” Other articles demonstrate how popular discussions about women’s rights had become at the time. An article from May 29, 1980 called “Salary Equity is Aim of NHCC Seminar for Women,” discusses how a man and a woman can have the same job and qualifications, but the man will still earn more money on average (Unknown 1980). The goal of this seminar was to teach women salary negotiation skills, in an attempt to lessen the wage gap (Unknown 1980). The fact that Ronald Reagan did win the 1980 election turned out to be a massive setback for the ERA, as the Republican party decided to remove its support for the amendment (“The Equal Rights Amendment” n.d.). This spurred ERA supporters to increase their efforts, and as a result, national discussion of the ERA was heightened in 1981 and 1982. Despite this, the ERA remained three states short of ratification by the June 30, 1982 deadline, which effectively killed the bill (“The Equal Rights Amendment” n.d.).

It was in this environment, with both pro and anti-ERA groups attempting to either kill or pass the amendment by the 1982 deadline, that the ERA affected female representation in Under Construction during the early 1980s. To understand how this happened, we must first take a comprehensive look at who the magazine was representing in the issues between 1980 through 1983. The Fall 1980 issue of Under Construction is where we will begin. The literary advisor of this issue was Dyan McClimon, and the art advisor was Frank Schreiber. The literary section of the Fall 1980 issue of Under Construction only contains eight short stories, and no poetry. This issue is also made up of stories with disparate themes. The longest story is called “Grady” by Jack U. Bell, and is about the title character and his time stationed in the Philippines during World War II. The story details how Grady would dig holes on the island base where he was stationed to hide his beer stash in case resupply shipments were late. Despite this, Grady proves to be very heroic, and stays cool under pressure when a rookie radio operator is electrocuted. The narrator also finds out that, after Grady’s wife died, he refused to be promoted to any rank higher than Private First Class, despite deserving promotions after he had earned a Purple Heart, three Silver Stars, and a Navy Cross (Bell 1980).

Although 62.5% of the stories in the 1980 issue of Under Construction are authored by women, the only story with feminist themes is called “Shana” by Marilyn Bahr. This story details the title character’s relationship with her abusive husband Denny. Shana spends most of her time cleaning her house because Denny rarely allows her to socialize, and has also forbidden her from working. Shana used to be an art teacher and she misses it. One day a neighbor comes to her door and asks if Shana would like to teach art for a summer festival the town is throwing. Shana hesitantly agrees, knowing that Denny will not like it. The neighbor gives Shana a bundle of art supplies and leaves. When Denny comes home later that evening, he flies into a rage and violently beats Shana while throwing the art supplies around the room. In self-defense, Shana stabs him to death with a pair of scissors that had come with the art supplies (Bahr 1980).

The other stories that make up the Fall 1980 issue of Under Construction consist of an essay about how to write well, a twist on the Hansel and Gretel fairy tale, an essay about human potential, a story about attending protests, a story about a beloved horse’s death, and a story about a private investigator. The themes of these stories vary a great deal, meaning there is no cohesive theme that unites this issue of Under Construction. The feminist themes found in the story “Shana” make up 12.5% of the themes for the entire issue. There is also more emphasis placed on the story “Grady” than any of the other stories, because of the way the editors chose to lay this story out in the issue. “Grady” begins on pages five and goes through to page eight, but is then cut in half, with the remaining pages occupying pages 51 through 55. There are no more stories after the end of “Grady,” so if the 1980 issue is read through in chronological order, the end of “Grady” is the story you are left with. This story was published in Under Construction the same year as the 1980 election. It was also published at a time when the national discussion of women’s rights and the ERA was very popular. This story highlights the male dominated world of the military during World War II, when gender roles were much stricter compared to the 1980s. “Grady” seems to highlight the idea that the military is a domain that should solely belong to men, at a time when opponents of the ERA were arguing that passage of the amendment would lead to women being drafted. The story “Grady” also serves to demonstrate how much female representation in the magazine would change after 1980, because (in all of the subsequent issues of Under Construction after 1981) emphasis was instead placed on stories authored by females or which included feminist themes.

When comparing the Fall 1980 issue of Under Construction with the Winter 1981 issue, it is clear that female representation and stories with feminist themes pick up a great deal. One example of a story with feminist themes from the Winter 1981 issue is called “BNE 803” by Heidi Myers. The title refers to the license plate number of a Jeep that stalks a young woman walking home after work late one night. As the woman gets closer to home, she sees the same blue Jeep over and over again, which begins to escalate her terror. Finally she manages to make it inside her house without the Jeep’s driver noticing where she lives. However, the Jeep circles her block several times. Eventually she calls the police to report the incident, but no patrol cars come over the next hour. Finally she decides to drive to the police station, and is chased by the Jeep again. When she finally gets inside the police station to file a report in person, the female dispatcher and the male police officers are apathetic to her distress (Myers 1981). This story highlights one woman’s experience of not having her concerns taken seriously. This is reflected in arguments by proponents of the ERA, who believed that the amendment would help legitimize women’s issues, and give women legal recourse when faced with gender discrimination.

Another story with feminist themes in the Winter 1981 issue is called “NHCC Causes Banning of Pot Roast” by Carol Moler. This is a non-fiction story from Moler’s life detailing her decision to return to school. Moler had grown up during the 1950s when expectations for women had been much different. She had adhered to the prescribed female gender roles of her day by getting married after high school and staying home to raise her children rather than pursuing a career. Every Wednesday for the past 15 years she had made a pot roast. However, once she decided to pursue a college education, she was no longer able to fit a weekly pot roast into her schedule. Moler’s husband adapted by learning to cook, and Moler herself was now able to help her daughter with math homework. The most important thing to come of the experience for her was greater self-esteem and a feeling of accomplishment (Moler 1981).

Because of her decision to go back to school, the gender roles for Moler and her husband are reversed, with Moler helping with math homework and her husband making dinner. This story can be seen as a direct challenge to the idea that passage of the ERA would threaten the structure of the American family. Moler shows that some changes are for the better, by showing that her and her husband are able to adapt to her spending more time outside the home. Going to school has also allowed Moler to become a more positive role model for her daughter. She was worried about learning math after being out of school for so long, but she is now able to help her daughter with her math homework (Moler 1981). This also shows that the fulfillment Moler experiences by raising her children is enhanced by gaining skills that will not only help her find a future job, but also deepens her relationship with her daughter, thus refuting the idea that women’s sole domain is in the home.

There are also several poems in this issue with feminist themes. One of them is called “Child of Mine” by Heidi Myers. This poem discusses an abortion which, it is explained, had to happen because the parents were much too young. Despite feeling that the abortion was necessary, Myers paints a picture of the complexity of the emotions that a woman has to grapple with for the rest of her life after making such a decision. She talks about these emotions hitting her out of nowhere, such as when she sees other people’s children and imagines how old her own baby would have been. This can be seen as a refutation of the anti-ERA argument that legal abortions would lead to women having them done casually. As seen in Myers’ poem, there is nothing casual about an abortion. Another poem with feminist themes is an untitled one by Sherry Wostrel. In this poem Wostrel discusses all of her roles, such as: wife, mother, daughter, housewife, cook, career woman, and student. She elaborates briefly on each role with two short lines. The lines after wife read, “submissively independent, married to Jeff six years.”, and the lines after housewife reads, “with grim determination I cook, and clean, and wash the clothes (Wostrel 1981).”

The stories and poems detailed above from the Winter 1981 issue of Under Construction are examples of how this issue greatly expanded the amount of female representation and feminist themes when compared to the Fall 1980 issue. All of these literary works represent real issues faced by women at the time, and women today. There were a total of 31 literary works in this issue, and of those, ten of them contain feminist themes. That is a jump from feminist works comprising 12.5% of the Fall 1980 issue, to comprising 32.3% of the Winter 1981 issue. In addition, 80.6% of the literary works in this issue were authored by women, regardless of whether they had feminist themes or not, which is an increase from the 62.5% of female authored works in the Fall 1980 issue.

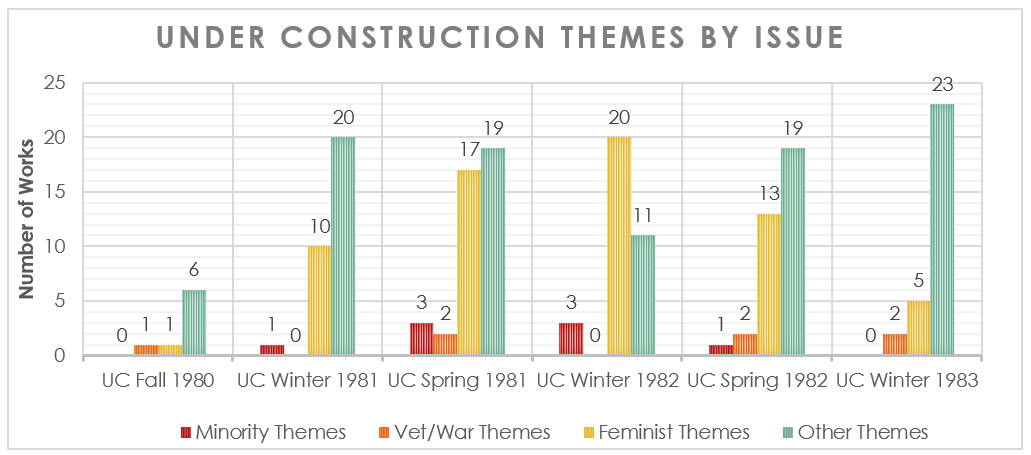

The tables below helps to illustrate the fluctuation in both female representation and feminist themes in Under Construction between 1980 and 1983.

Table 1--Under Construction Themes

Table 2--Gender of Authors

One of the big differences between the Fall 1980 issue of Under Construction and the Winter 1981 issue is that there was a complete change in the faculty advisors. Dyan McClimon had been the literary advisor in 1980, but by Winter 1981 Vicky Lettmann had taken over that role. She would continue to be the literary advisor until the end of 1982. Likewise, Frank Schreiber was replaced by Lance Kiland in this issue. The change in faculty advisors was accompanied by a new mission statement being placed in the beginning of this issue, in which the advisors state that they would like to better reflect student interests and be more “responsive” to the North Hennepin community (Lettmann and Kiland 1981). It makes sense that the advisors would choose to accomplish this by increasing the amount of feminist themes and female representation in the magazine because, by 1981, women made up 58% of the student population (Wavrin 1983) (see Table 1 and 2).

The trend of increasing feminist themes and female representation continued in the Spring 1981 issue of Under Construction, with 41.5% of the literary works containing feminist themes, and 83% of the literary works being authored by women (see Table 1 and 2). A poem by Heidi Myers called “Who For us Men” discusses the underrepresentation of women in the clergy of her church. In this poem she says that she believes in God, but was confused about why men are the only gender with higher positions in the church. Distraught about this, she asks a Christian man at her church to explain this to her. He replies that God has provided a role for everyone, and a woman’s role is to nurture children. He then points at his “crippled” hand and says that this is his “cross to bear.” To Myers, this is understood to mean that her female body is considered “crippled” as well. She concludes the poem by explaining how she still believes in God, but no longer attends church with her parents (Myers 1981). This is one woman’s story about the inequality she has experienced because she is female, which reinforces the reasons why proponents of the ERA believed that an amendment to the constitution promoting gender equality was necessary in the first place.

Another story from Spring 1981 with feminist themes is called “My Fat Syndrome” by Carol Moler. In this story, Moler discusses how she struggled with her weight until age 30. Moler talks about the challenges she faced as she entered adolescence and began to be interested in boys. One particular incident she remembers is asking a boy to a dance, and having him tell her afterwards that he only agreed to go because their mothers were friends. He also tells her that she would be a great girl if she wasn’t so fat. This event was the catalyst for Moler’s decades’ long experimentation with unhealthy crash diets. The only way she was able to break this cycle was by coming to NHCC and taking a nutrition class (Moler 1981). When compared to Moler’s work in the Winter 1981 issue of Under Construction, it is clear that she not only found personal fulfilment from attending North Hennepin, but she was also able to improve her health as well. She would not have been able to do this if she had not decided to go back to school in order to work outside of the home.

We finally see feminist themes and female representation in Under Construction reach its peak in the Winter 1982 issue, with 58.8% of the literary works containing feminist themes. This number also happens to be the percent of women in the student population at the time. Thirty-two of the Thirty-four literary works in this issue, or 94%, are also authored by women regardless of theme (see Table 1 and 2). One example of a poem with feminist themes is by Sherry Lee, and it discusses her feeling of being held back by her “husband’s demands” and her “children’s needs” (Lee 1982). This makes her feel like she is unable to be spontaneous because she does not have any free time (Lee 1982). Lee ends this poem by saying that, “She allowed others to enslave her. She had no self” (Lee 1982). Another poem with feminist themes is called “Portraits” by Carol Moler. In this short poem, Moler compares the differences between how men and women related to each other in the past and present. She claims that women of the past had to look up to their husbands, but the women of the 1980s were able to look at men eye-to-eye, and were able to take care of themselves (Moler 1982). A third poem that deals with feminist themes is called “Ms. Muffet” by Brigid M. Quinn. This poem is a reimagining of the children’s rhyme Little Miss Muffet, only this time Miss Muffet confronts her spider problem head-on instead of running away from it (Quinn 1982). These poems all deal with women and how they see themselves. Lee’s poem expresses the feeling that she is no longer in control of her life, while Moler and Quinn’s poems express the liberation they feel because they can take care of themselves.

By the Spring of 1982, female representation and feminist themes begins to decline in Under Construction. Literary works with feminist themes dropped to 37% in this issue, while 72.2% of the literary works were authored by women (see Table 1 and 2). This reduction in feminist themes lines up with the timeline of the ERA, which had failed to be ratified June 1982. However, there are still many examples of feminist works in this issue. One story called “A Memoir, and Much More” by Leslie Keyes lays out the details of her mother’s life. She had grown up at a time when keeping a clean house was seen as being one of a woman’s highest achievements, but Keyes’ mother doesn’t keep up with that anymore. Neighbors stare at her unkempt lawn and judge her as being lazy, but that is not the case. Her mother has just come to the conclusion, after a very difficult life which included being raped twice, that keeping up appearances does not really solve anything (Keyes 1982).

The next issue of Under Construction from the Winter of 1983 continues this downward trend for feminist themes, with only 16.7% of the literary works containing them. However, female representation has slightly increased in this issue, with 76.7% of the literary works authored by women (see Table 1 and 2). It is notable that the feminist themes have declined in this issue, because 1983 was the year after the ERA had failed to be ratified, and was also one year away from the ERA being reintroduced into Congress in 1984. One of the most notable examples of a story with feminist themes in this issue is called “A 50’s Feminist Has Empathy for Man” by Carol Moler. In this story, Moler discusses the gender roles of the 1950s and details how they had changed by the 1980s. She observes that women’s roles had greatly expanded by 1983, including the expansion of women into the work force. Moler explains how this was difficult for men from the 50s to adjust to, since their identities had previously been defined by being providers. More women focusing on their careers also meant that men from the 50s were now being asked to take more responsibility for raising their children, which had previously been the sole domain of women (Moler 1983). This suggests that, as women’s roles expanded, men perceived their roles as shrinking, which can help explain some of the backlash against the ERA, and why it had failed to be ratified.

While the national discussion surrounding the ERA seems to have had a more subconscious effect on the types of stories women were writing in the early 1980s, the literary advisor Vicky Lettmann seems to have played a more deliberate role in getting these types of stories published. One hint Vicky Lettman consciously decided to increase female representation when she took over as literary advisor in 1981 is her response to a review of Under Construction by English faculty member Al Calvin. In the May 21, 1981 edition of the student newspaper the North Star, Calvin offers a lukewarm review of the literary works in the Winter issue of Under Construction from that year. The title of the article reads: “Under Construction Proves Some Writers Shouldn’t be Published.” Calvin elaborates on this title in his review, where he accuses the magazine of choosing quantity over quality when it chose what to publish in the Winter 1981 issue (Calvin 1981). He also notes that there were five times more female authored stories than male authored stories in this issue, and claims that increasing the number of stories published by men would have made the issue more balanced (Calvin 1981). Vicky Lettmann responds to this criticism in the same issue of the North Star by asking Calvin why there are so many more male writers published in his anthologies than women writers (Lettmann 1981). She also insists that Calvin read Silences by Tillie Olsen, which is an example of feminist literature that discusses how being a woman and a mother has held female writers back historically (Lettmann 1981). This suggests that Lettmann was intentionally trying to create a space for female representation in the Winter 1981 issue of Under Construction, which was especially important at a time when ERA advocates and feminists were trying to get women’s concerns taken seriously.

Certainly Vicky Lettmann played a role in deciding who would be represented in Under Construction while she was literary advisor between Winter 1981 to Spring 1982. In her paper, Sam Savela elaborates on the influence an advisor can have on who gets represented in Under Construction by looking at the impact Michael Fedo had on the issues that came out from 1970 to 1974. She states that, “Under Construction continued to present itself as a platform for students to represent themselves through literature of their choosing, but the actual publication represented students through literature of Fedo’s choosing” (Savela 2010). However, this situation does not seem to be the case while Vicky Lettmann was literary advisor during the early 1980s. The stated goal in the Winter 1981 issue of Under Construction was to better represent student interests, and with 58% of the school population comprising of females that year, it follows that an interest in feminist issues would be prevalent among the school population. However, before Lettmann was replaced as literary advisor in 1983, the amount of stories with feminist themes had already declined in the Spring 1982 while she was still the advisor.

When the timeline for the history of the ERA is compared to the changes in female representation and feminist themes present in Under Construction between 1980 to 1983, it is clear that the ERA played the biggest role in this fluctuation. So while Vicky Lettmann may have been the person to initiate the increase in female representation after she became literary advisor in 1981, she was clearly following the student population’s interest in the subject of feminism at the time. After the Fall 1980 issue of Under Construction, female representation and feminist themes pick up dramatically. For all three issues published between the Winter 1981 issue of Under Construction to the Winter 1982 issue, female representation and feminist themes are greater than in the previous issue. The peak of female representation and feminist themes occurred in the Winter issue of 1982, right as the deadline for the ERA ratification was coming up. After the amendment failed to be ratified, the amount of stories with feminist themes declined, and by Winter 1983, it hit a level close to the one seen in the 1980 issue of Under Construction. It seems that with the death of the ERA student interests had moved on from feminist ideals, though female writers still made up a large portion of the contributors for the Winter 1983 issue. When the timelines are compared, it is clear that the rise and fall in interest in the ERA mirrors the rise and fall in feminist themes in Under Construction.

Reference List

Bahr, Marilyn. 1980. “Shana.” Under Construction, Fall.

Bell, Jack U. 1980. “Grady.” Under Construction, Fall.

Calvin, Al. 1981. “‘Under Construction’ Proves Some Writers Shouldn’t Be Published.” North Star, May 21.

Keyes, Leslie. 1982. “A Memoir, and Much More.” Under Construction, Spring.

Lee, Sherry. 1982. “Untitled.” Under Construction, Winter.

Lettmann, Vicky, and Lance Kiland. 1981. “Untitled.” Under Construction, Winter.

Lettmann, Vicky. 1981. “Too Critical.” North Star, May 21.

Moler, Carol. 1983. “A 50’s Feminist Has Empathy for Man.” Under Construction, Winter.

———. 1981. “My Fat Syndrome.” Under Construction, Spring.

———. 1981. “NHCC Causes Banning of Pot Roast.” Under Construction, Winter.

———. 1982. “Portraits.” Under Construction, Winter.

Myers, Heidi. 1981. “BNE 803.” Under Construction, Winter.

———. 1981. “Child of Mine.” Under Construction, Winter.

———. 1981. “Who for Us Men.” Under Construction, Spring.

Quinn, Brigid M. 1982. “Ms. Muffet.” Under Construction, Winter.

Savela, Sam. 2010. “The Disconnect Between Under Construction’s Actual and Ideal Student Body Representation.”

Sievert, Donna. 1980. “Steinem Challenges Feminists.” North Star, October 30.

“The Equal Rights Amendment.” n.d. Equal Rights Amendment. Accessed August 2, 2019. https://www.equalrightsamendment.org/the-equal-rights-amendment.

Unknown. 1980. “Salary Equity Is Aim of NHCC Seminar for Women.” North Star, May 29.

Weber, Jill M. 2008. “Gloria Steinem, ‘Testimony Before Senate Hearming on the Equal Rights Amendment’ (6 MAY 1970),” 20.

Wostrel, Sherry. 1981. “Untitled.” Under Construction, Winter.

Appendix

Year Issue of Under Construction Stories in Issue ERA Timeline

1980 Fall – “Grady” by Jack U. Bell – “Shana” by Marilyn Bahr – 1980 election won by Ronald Reagan

– Election prompts public debate over the passage of the ERA

1981

Winter

– “NHCC Causes Banning of Pot Roast” by Carol Moler

– “BNE 803” by Heidi Myers

– “Child of Mine” by Heidi Myers

– “Untitled” by Sherry Wostrel

– Continued public debate about the passage of the ERA

– Pro-ERA groups continue to push for the three states that are needed to ratify the amendment.

Spring

– “My Fat Syndrome” by Carol Moler

– “Who for Us Men” by Heidi Myers

1982

Winter

– “Untitled” by Sherry Lee

– “Portraits” by Carol Moler

– “Ms. Muffet by Brigid M. Quinn

– Deadline for ERA is June 30, 1982

– ERA fails to be ratified. Short by three states

Spring – “A Memoir, and Much More by Leslie Keyes

1983

Winter

– “A 50s Feminist Has Empathy for Man” by Carol Moler

– 1983 is one year after ERA fails to be ratified, but one year before ERA is reintroduced to Congress in 1984.