by Ryan Tate

The presence of speakers on the campus of North Hennepin Community College has been extensive, and stands firmly significant throughout its rife forty-four year history. From its earliest beginnings in 1966, the college has demonstrated visitations from a wide array of U.S. political figures, varying from the most local city council member, to the highest office in American politics. While over time, there has been adaptation to political messages and means, these prevalent politicians have retained a consistent principle and running rationale. At times, the tone of these public officials appears to differ, but the larger message they have perpetually upheld throughout their frequenting of the campus encourages student engagement and support of political activism. Politicians spoke directly of activism in the 1960s,’70s and early ’80s. With the same underlying ambition, they have transformed and progressed in more recent decades into promoters of education and hikers on the campaign trail. Over time, politicians have understood and implemented the methods by which higher education and campaign tactics produce more participatory constituents. Through the support of student activism, promotion of higher education, and campaign stops at the college, politicians have essentially championed their long favored message: the encouragement of student political engagement.

The focus of politicians upon political activism has been evident since the college’s earliest beginnings. Past trends of political addresses have focused on the need for political activism directly. Former Vice President of the United States, Hubert Humphrey, appeared on the campus of what was then known as North Hennepin State Junior College in February of 1970. His visitation took place after he accepted the invitation to kick off the mid-winter Sno Daze, where he spoke alongside the performance of Canadian rock-band, The Guess Who (Brooklyn Park Post 1970). He addressed the audience for over thirty minutes, asking students to become a part of history by involving themselves in political activity. Humphrey referred to the ’60s as the “break point” and discussed economic issues of that time, with reference to his own experiences in the Great Depression (Kuehn 1970). Evidence of the time indicates that his message was not unusual.

Months later, in October 1970, Georgian representative Julian Bond spoke on campus. After his state legislature refused to seat him in 1966 because of his statements about the Vietnam War, Bond had to have the U.S. Supreme Court force them to allow him to take his elected seat. This incident created his reputation as a young, radical liberal. When Bond spoke to North Hennepin’s enthusiastic listeners, he was reported to have “chided college students and young people for their lack of political involvement.” His guest lecture touched upon topics of taxes, suggesting “cities tax people living in suburbs who commute” and the issue of bussing, which he advocated in favor of. His opinions were received with much approval (Brooklyn Park Center Sun 1970).

In 1974, Bond’s statements were echoed in their means for supporting engagement, when Minnesota Attorney General Warren Spannus appeared on campus; he too encouraged students to, “participate in public discussion of issues and work for the passage of good laws.” Spannus furthered his talks by “call[ing] for [government] recognition of several rights of citizens” (Osseo Maple Grove Press 1974).

While primarily a focus of political figures on the campus in the ’60s and ’70s, activism continued to play a role as a direct political message during the early ’80s. It was in the spring of 1980 that Ralph Nader spoke at North Hennepin Community College, where he impressed an audience of a thousand with his central theme of consumer involvement. Nader told his listeners that, “through united effort the public—and the public alone—has the potential to bring change in national policies and issues” (Shukle 1980). His speech focused on energy, transportation, pollution, and getting people involved (Celebrity Speaker Series 1980).

By 1983, the agenda for promoting activism began to reach its tail end. Bella Abzug, a former representative and the first woman in history to run for U.S. senate in New York, appeared on campus in March to discuss issues of her concern. Based on her legislative record, these issues likely included “mass transit, environmental legislation, and aid for the elderly and handicapped,” while concurrently promoting citizen involvement (Celebrity Speaker Series 1983). As records indicate, this was likely one of the last direct activism approaches from public officials on the campus of North Hennepin.

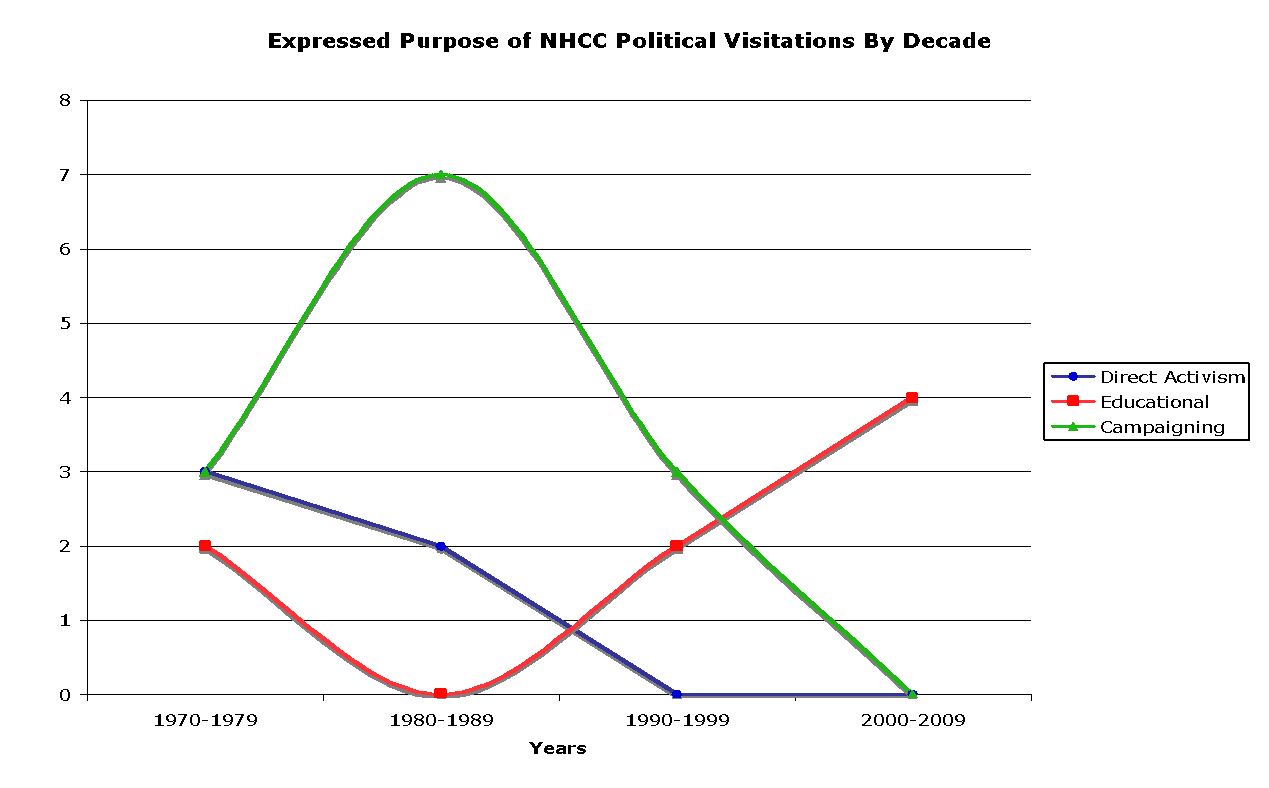

In terms of culture, the method for directly attempting to encourage activism in students is a reflection of the political climate. It has been noted that over time “legislators carefully track public opinion in order to win public support for their desired policies” (Jacobs and Shapiro 2000, 7). This suggests that the political movement away from activism and towards campaigning and education was likely a reflection of less public favor towards activism. It also implies that politicians recognized that higher education is likely to yield political engagement, as it is necessary to tap into social desires, attain votes, and to run on more popular platforms. This begs the question: Why would there be a need, either from officials or the public, to move away from the promotion of activism? It has been argued that “student political involvement has not been considered a legitimate form of politics either by the general public or the government” and really has created major political change (Altbach 1997, 6). Further analysis demonstrates that student activist movements have often been short lived, and have not grown into developed organizations (Altbach, 1997, 7). The impact of this existence, without larger versions of student political movements, has been both splintering of membership and of leadership, since students graduate and are distanced from their campuses and student-run groups (Altbach, 1997, 7). Therefore, in the ’80s, there was a shift in political approach—from promoting activism, toward campaign and educational emphases, as seen in Figure 1.

Furthermore, research shows that “government politics in the 1980-93 period was less consistent with the preferences of the majority of Americans, than during the 1960-79 period” (Jacobs and Shapiro 2000, 4). This illustrates that during this time, legislators were either less responsive to American needs, less informed by a slow-down in activism (which would designate activism as having actually been effective), or were guilty of trying to mold constituents around their agendas, rather than the other way around. Whatever the reasoning may be, it is important to note the transition, and recognize that there remained a political necessity to promote student engagement beyond the activist promotional slow-down. Consequently, education and campaigning, as methods for encouraging activism, were drawn to the forefront of political rhetoric on campus.

As it has been noted in previous studies, the notion that education fosters greater civic involvement remains largely uncontested (Hillygus 2005, 25). As a result of accrediting educations’ ability to indirectly encourage constituent engagement, the movement toward education has increased in recent decades. Many post-1980s political figures have approached their visits to the campus of North Hennepin with agendas focused primarily on promoting education and aligning themselves with these reflective political platforms.

The late Senator Paul Wellstone was one of the numerous officials on North Hennepin’s campus promoting educational causes. Wellstone was a politician with deep educational roots, having been a professor of political science at Carleton College for a number of years prior to his entry into the public domain. He often joked with North Hennepin Community College president Ann Wynia that after leaving the senate, he hoped she would hire him, since he had long dreamed of teaching at a community college. He came to the campus at least three times to promote education for all of its values, including once as a graduation speaker for the class of 1995 (Wynia 2010). The ability of education to produce more concerned political participants is something which cannot be ignored, and Wellstone was clearly aware of this, given his politically affiliated professions. While the promotion of education was on Wellstone’s campus agenda (Wynia 2010), his direct openness in support of a politically active student body played a role in this recognition as well. Wellstone was fond of engaged students, having seen positive effects from active students both as a professor facing potential dismissal (Wellstone 1999, 6), and as a candidate who was said to be carried on their shoulders to victory (Wellstone 1999, 22). This was ultimately a matter close to his own political career.

Education is a social concern that has attracted both sides of the American political spectrum. Long time former Representative Jim Ramstad, who served on Minnesota’s Congressional District Three for almost eighteen years, was awarded by both North Hennepin and Anoka Ramsey community college in April of 1997, in recognition for his long-standing commitment and support of TRIO programs (US Fed News Service 1997). These programs work to provide services for disadvantaged individuals (Office of Postsecondary Education 2010). Many local Republicans at the time, including Ramstad, saw the appeal of speaking directly to their constituents, and thus visited the college often (Wynia 2010). This seems like a worthy motivation considering that these constituents, because of their involvement in furthering education, are more than likely to become politically engaged.

Other politicians have also brought about awareness for political activism through education. Representative Keith Ellison’s presence at North Hennepin in 2008 demonstrated an educational focus during campus events in regards to Black History month (Wynia 2010). Despite being outside of his own Congressional District Five, North Hennepin was attended by over two thousand of his constituents (Office of the Chancellor Research and Planning 2007). Since Ellison is an African-American and the first Muslim to be seated in the U.S. House of Representatives, his visit supported more favorable political engagement for minorities. Ellison’s presence encouraged cultural awareness and a more tolerable social and political atmosphere.

Politicians on North Hennepin’s campus also include the visit of Senator Amy Klobuchar in 2009 (Wynia 2010). Klobuchar approached the college and initiated the visit to promote President Obama’s “ambitious ten-year initiative to strengthen the economic role of America’s community colleges”; she progressed this by using the meeting and speech as a roundtable to discuss plans to strengthen federal support for community colleges (Hometown Source). Her intentions, which echoed that of President Obama’s, seemed logical in that community college enrollment was increasing at more than twice the rate of enrollment at four-year colleges (Hometown Source). These growing constituents garnered a need for political participation. Senator Klobuchar used economic incentives, citing that college-graduate unemployment stood at about half of the national average (only about four percent), as one of her many points to emphasize a greater need for an educated populous (Klobuchar 2009). However, the senator was not alone in her endeavors to recognize the importance of education for the greater concern over civic involvement.

Other educational acknowledgements have come from Ramstad’s congressional successor, Erik Paulsen. While Paulsen has never given an official address to the student body, he has met with community college representatives, namely NHCC president Ann Wynia, Normandale president Joe Opatz, Anoka Ramsey president Pat Johns, and Hennepin Technical president Cecilia Cervantes, to discuss educational initiatives. His meeting with these college heads led to his receipt of a Certificate of Recognition honoring his commitment to higher education (Congressman Erik Paulsen 2010). While it is true that this was not a campus political visitation, it serves to demonstrate bipartisan recognition for the importance of higher learning.

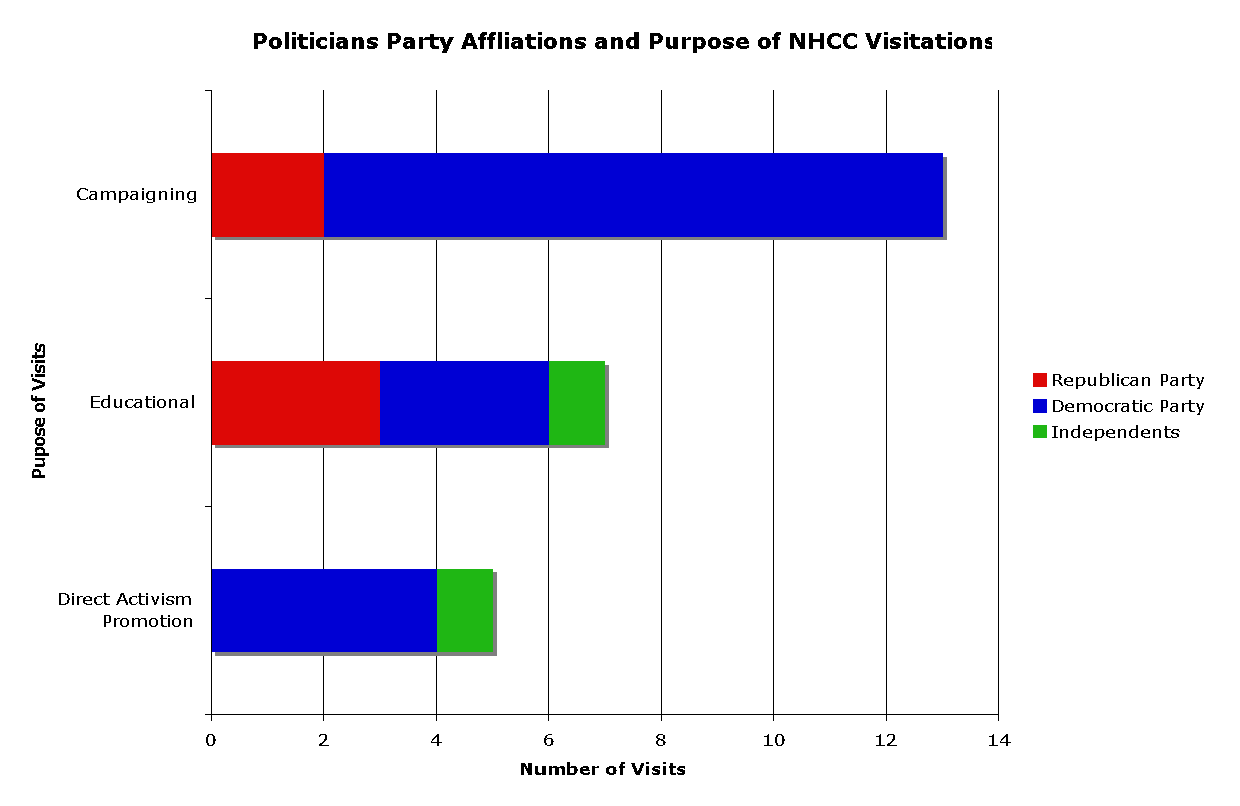

Politically, using education for establishing involved citizenry is simply a different take on an old concept. Education stands as a politically favorable platform, as noted in its representation on the North Hennepin campus in the most bipartisan fashion, especially in comparison to other visiting purposes. This is demonstrated in Figure 2.

While education can at times seem unfavorable, especially considering recent difficulties for state appropriations, these results are more dependent upon altered educational outlooks than they are on educational unpopularity. Sometime in the late 1970s, when there was a shift in focusing on how higher education benefits individuals, there was an evident movement from previous focuses like state appropriations and scholarships (which stood as a responsibility of society), to student loans and tuition (burdens upon the individuals) (Heller 2001, 6). This has impacted educational outlooks from being largely considered a social good and responsibility, to now an individual good and responsibility. The future of this topic on campus will serve of interest as pending legislation hopes to, “reduce the need of students to depend on non-federal, high-interest private loans and increase Pell Grants” (Klobuchar 2009). However, the progression from viewing social activism for society’s benefit, to educational pursuit for the individual’s benefit, has not altered the focus to bring about political participation. (Heller 2001, 6). Largely, these two means bring about similar results, due to the fact that education, like activism promotion, stands as a primary mechanism behind many citizenship characteristics (Hillygus 2005, 25). It is interesting to note that there seemed to be a somewhat seamless transition of issues that politicians discussed at North Hennepin beginning in the 1980s, from activism to education (Refer back to Figure 1).

The impact of education on political participation is widely studied, and some research has even indicated that larger civic education in subjects associated with the humanities and social sciences leads to more political engagement (Hillygus 2005, 39). Furthermore, there has been evidence that there is “congruence between the characteristic political orientation of different disciplines and political beliefs of entering students who plan to major in them” (Lipset 1966, 5). In this sense, it seems necessary for involvement from both sides of the political aisle. Indeed, this has often been the case at North Hennepin Community College, where numerous humanities and business courses are offered. Many politicians promote education and attend events on college and school campuses across the country—North Hennepin being one example—and education acts as a large section of political platforms at every level of government and across political spectrums. This is demonstrated through the college’s hosting of state Attorney Generals and state representatives, to national figures of both parties. This suggests that education is a beneficial political platform, and also a vehicle for the encouragement of political participation.

Another method for promoting activism that candidates have continued to rely upon consistently throughout the history of North Hennepin is that of direct campaigning. Campaigning works in that it is an age-old method for yielding engagement from constituents. Results in higher education institutions are exceptional, in that they are more likely to be willing to politically participate.

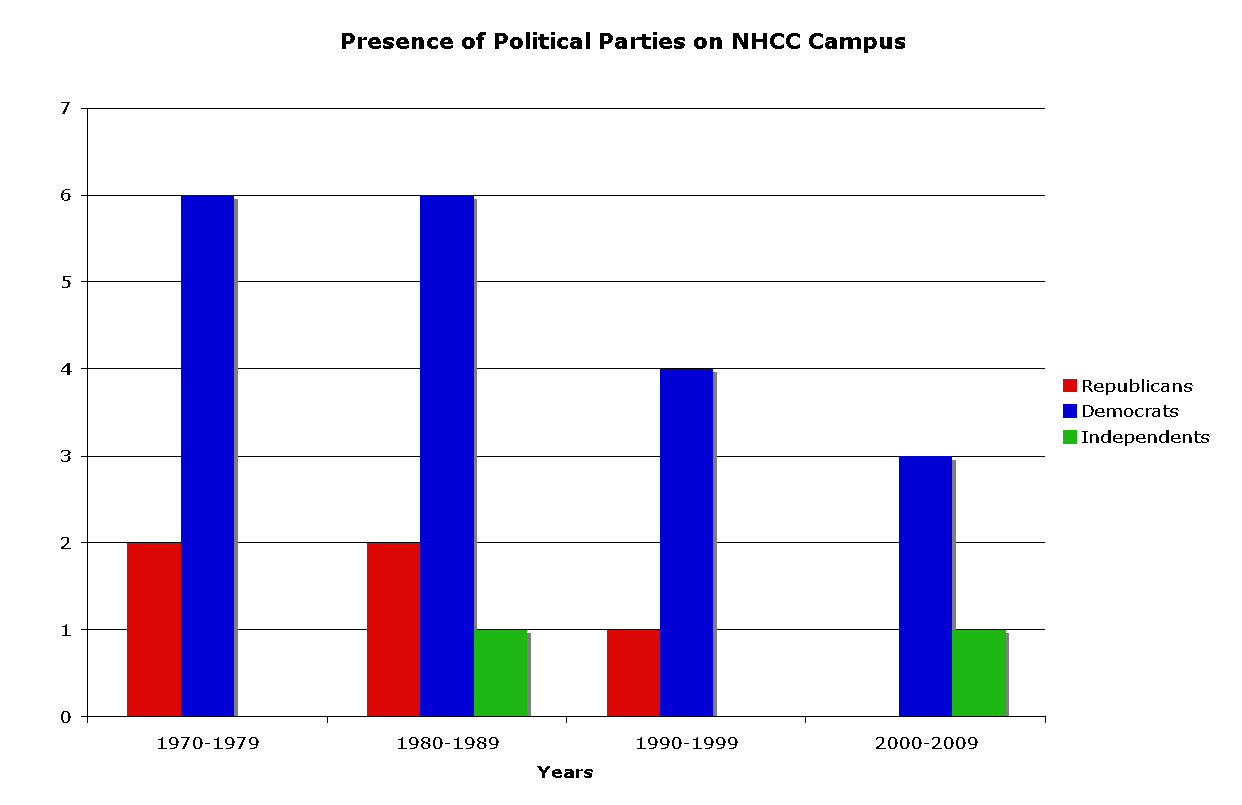

Back in the years of North Hennepin’s beginnings, in July of 1970, DFL endorsed candidate George Rice appeared on the campus of North Hennepin to speak with students, faculty and the general public about issues regarding his campaign (North Hennepin Post 1970). A long list of politicians followed suit, as observed in Figure 3.

Then Senator Walter Mondale visited the college in May of 1972, within months of his own re-election day that November (North Hennepin Post 1972). Mondale’s decision to appear on campus in the delicate months of an election season demonstrate a primary use of the grounds for campaigning. This proved to be successful, as he returned to Washington later that year.

In 1984, the Student Senate of North Hennepin Community College encouraged the presence of political candidates on campus when they invited seven different contenders for office, including Bruce Vento (DFL), Bill Frenzel (R), Gerry Sikorski (DFL), Martin Sabo (DFL), Joan Grove (DFL), Dave Peterson (DFL) and Mary Jean Rachner (R) (NHCC Retrospect 1984). All of these figures were running for office in November and appeared for a series of talks, which focused primarily around their own campaigns. Of the seven, at least four returned to office (NHCC Retrospect 1984).

In November 1994, President Bill Clinton and then First Lady Hillary Clinton visited the campus of North Hennepin to campaign for a crowd of more than 1,700 people, at an event open to both students and the general public (McGrath and Baden 1994). The White House’s choice of locale was noted for its connection to then DFL candidate, and long-time NHCC President, Ann Wynia. Both Clintons’ speeches focused solely upon campaigning and worked to “stump” for Wynia’s race against Republican Rod Grams (Baden and McGrath 1994). While the visit was short, the Clintons’ uses of campaign tactics were directly related to a desire for greater political participation from constituents, especially in favor of the Democratic Wynia. While the fate of the election itself may not have experienced the positive impact of the visit for the DFL candidate, the political use of educational grounds for campaigning to indirectly promote activism, particularly amongst students, followed a long tradition.

Politicians have made use of North Hennepin Community College for the purpose of campaigning because it is a method designed to increase voter turnout, especially in the candidate’s own favor. Campaigning, like promoting activism and education, encourages political engagement, except rather than being aimed toward specific issues, it is aimed toward specific people—or parties. Like other political purposes discussed, campaigning demonstrates the need for participation from constituents. Approaching a campus to stump for an election is an identifiable method for promoting activism. Campaigning directly plays upon this idea and makes use of campaign stops. While there appears to have been a recent slow-down in campaign rhetoric on campus, it is not likely to remain permanent. Campaigning is an old, familiar and long proven method that extends beyond politics and into fields of public relations, mass communications and advertising. However, the slow-down in favor of educational promotion should be noted, as it may reflect a popular citizenry preference for candidates promoting specific substantial issues.

Over the history of North Hennepin Community College, Democrats have largely been the ones to take most advantage of the campaign method. Their overall presence has been more significant than that of Republicans or Independents combined (Refer to Figure 3). Recent evidence has shown a drop of 10% points, from 2001 to 2009, of the number of college graduates who hold a “Republican Party affiliation and leaning” (Jones 2009). This change could either act as the purpose behind more Democratic visitations on campus, or could indicate the result of them. Either way, the future of Republican educational visitations will need to rise to meet these new and changing constituent bases.

However, this Democratic presence is also in large part due to the greater resonation of North Hennepin with what appears to be a more Democratic constituent base. North Hennepin is an institution that prides itself on diversity, its focus on affordable education, and providing equal access to the American Dream. Not only are these characteristics relatable to Democratic platforms, but the college also lies within a liberal area of Congressional District Three. Brooklyn Park, Minnesota, the city in which North Hennepin Community College is located, has 17.3% more minorities than the rest of Congressional District Three, and a median household income that is $4,280 lower than the rest of the district (U.S Census Bureau 2000). This aligns with typical national party demographics, which see Democrats representing roughly 25% more minorities than Republicans (Newport 2009), and statistically fewer constituents when median household incomes are greater than $30,000 annually (Pew Research Center for People and the Press 1996). North Hennepin also has many students attending from Minnesota Congressional District Five, which is heavily Democratic and would likely further enhance these figures on campus (Office of the Chancellor Research and Planning 2007).

Often times, politicians, especially those who are local, have spoken at the institution simply because speaking with constituents is a good thing. Jim Ramstad’s presence on the campus, along with many other political figures including Bill Frenzel, Bruce Vento, and Amy Klobuchar, has demonstrated this need to see and be seen directly among local constituents (Wynia 2010). This establishment in the public eye is prevalent on college campuses, partly due to the understanding that students, through their education, are more than likely to emerge as future generations of voters.

Political speakers on the campus of North Hennepin have retained a principle of political engagement throughout their visits. Through speaking of activism directly in the first half of the college’s history, and progressing into recent decades as promoters of education and campaign politics, the same aspect has been evident. Greater activism equals larger levels of participation, and higher education and campaign tactics also produce more involved constituents. It is through these means that the college has witnessed progressions of political topics among those public officials speaking at campus events. These message adaptations are not without reason. As promoting political activism during the 1960s, ’70s and early ’80s grew out of sync, partially from proving to be less than effective (Altbach 1997, 6), politicians recognized the standing ability of education to maintain a more permanent ability to keep constituents engaged and predict “characteristics” (Hillygus 2005, 25). As a result, political commentary moved in the educational direction and became a more favored means for obtaining civically motivated citizens. Campaigning has also rendered itself with frequency at the college over the years (Refer back to Figure 1), especially during the transition period from activism promotion to educational focus during the 1980s. Campaigning is likewise influential to political engagement, except rather than being geared toward specific issues in the ways that activism and education are, it is geared toward specific people and parties. In the end, these purposes are important to identify, as they reveal much about the greater social, political, and educational climates under which they occur. This reasoning also stands to demonstrate the role in which education plays in politics, and politics plays in education. It is with that, that politicians visiting North Hennepin Community College have ultimately held the same message, despite their differing tones.

References

Altbach, Philip. 1997. Student Politics in America. Transcription Publishers.

Baden, Patricia Lopez and Dennis J. McGrath. 1994. “Senate Hopefuls Get in Closing Hits – but Voter Attention Waning.” Star Tribune, November 7.

Brooklyn Park Center Sun. 1970. “Bond Warns of Growing Gap, Georgia Legislator Speaks at College.” October 14.

Brooklyn Park Post. 1970. “Humphrey at JC Sno Daze.” January 29.

Celebrity Speaker Series. 1980. “Ralph Nader.” March 11.

Celebrity Speaker Series. 1983. “Bella Abzug.” March 3.

Congressman Erik Paulsen. 2010. “Paulsen honored by MnSCu for commitment to higher ed. U.S. House of Representatives.” http://paulsen.house.gov/index.cfm?sectionid=154§iontree=21,154&contentid=444.

Heller, Donald E. 2001. The States and Public Higher Education Policy: Affordability, Access, and Accountability. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hillygus, D. Sunshine. 2005. “The Missing Link: Exploring the Relationship Between Higher Education and Political Engagement.” Political Behavior. 1: 25-47.

Hometown Source. “Klobuchar to highlight federal plans to strengthen colleges.” ECM Publishers, Inc. http://hometownsource.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=….

Jacobs, Lawrence R., and Robert Y. Shapiro. 2000. “Politicians Don’t Pander: Political Manipulation and the Loss of Democratic Responsiveness.” Studies in Communication, Media, and Public Opinion. Chicago, IL.: University of Chicago Press.

Jones, Jeffery M. 2009. “GOP losses span nearly all demographic groups.” Gallup Polling. May 17. http://people-press.org/report/?pageid=465

Klobuchar, Amy. 2009. Videoclip, directed by NHCC faculty/staff. Brooklyn Park, MN: 2009, videoclip. Accessed February 2010. http://www.nhcc.edu/main/NHCCNews/Channel12_Klobuchar.aspx

Kuehn, Eileen. 1970. “Political Activity Urged by Humphrey in College Speech.” Brooklyn Park Center Sun. February 4.

Lipset, Seymour Martin and Philip G. Altbach. 1966. “Student Politics and Higher Education in the United States.” Comparative Education Review 10: 320-349.

Newport, Frank. 2009. “Republican Base Heavily White Conservative Religious.” Gallup Polling. May 1-27. http://www.gallup.com/poll/118937/Republican-Base-Heavily-White-Conserv….

NHCC Retrospect. 1984. “Here and There on Campus.” Fall Semester.

North Hennepin Post. 1970. “George Rice to speak at North Hennepin.” July 23.

North Hennepin Post. 1972. “Visit Campus Soon.” May 4.

Office of the Chancellor Research and Planning. 2007. “Enrollment by Institution and Minnesota Congressional District: Fiscal Year 2006.” Minnesota State Colleges and Universities, October 30.

Office of Postsecondary Education. 2010. Federal TRIO programs. U.S. Department of Education, April 24. http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ope/trio/index.html.

Osseo Maple Grove Press. 1974. “Spannus Speaks at North Hennepin College.” May 5.

Pew Research Center for People and the Press. 1996. “Survey Reports: Republicans.” August 7. http://people-press.org/report/?pageid=465.

Shukle, Carol. 1980. “Nader talk focuses on favorite themes: nuclear energy, oil companies, auto makers among targets.” Newspaper Clipping. May 20.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2000. “Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000. Geographical Area: Congressional District 3, Minnesota (106 congress).” University of Minnesota Library. Accessed April 30, 2010. http://govpubs.lib.umn.edu/census/profiles/5002703.pdf.

U.S. Fed News Service. “Representative Jim Ramstad to be Recognized at National TRIO Day Celebration.” HT Media Ltd. Accessed February 28, 2010. http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1P3-1239295811.html.

Wellstone, Paul. 1999. The Conscience of a Liberal: Reclaiming the Compassionate Agenda. New York: Random House.

Wynia, Ann. 2010. Interview by Ryan Tate. Brooklyn Park, MN. February 17.