by Aleia Wilbur

The recent death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg has caused many people across the nation to examine the past of feminism, as well as what it might look like in the future. While many people today consider themselves a “feminist,” some of them are lacking knowledge about the rich history that has shaped women’s rights today. In the past year alone, we have seen the community of African American women organize over the murder of Breanna Taylor. Also, it is possible that by 2021 we could have the first ever female vice president. These recent steps in women’s rights would not have been possible without the sustained efforts of women and men in the past century. Among those efforts are what Lorna Finlayson, a Philosophy professor at the University of Essex, calls “waves.” Waves are a common way to describe the history of feminism, and the differentiation helps show change over time. There are three agreed upon waves, with a possible fourth wave being debated (Finlayson 4-5). The second and third waves of feminism were different from each other in the aspects of the issues they faced, their goals, significant occurrences in the movements, and their accomplishments.

Early History of Feminism

The fight for women's rights has been present in America since 1848. However, the term “feminism” did not start until late the 1880s. Feminism, as a general definition, is the advocacy for the idea that there should be equality of the sexes in all areas of life (Finlayson 3). In 1848, the first women’s rights meeting was held in New York. After this, waves of women with different goals in mind pushed for rights in America. The first wave is a wide period of time from when feminism first began up until the passing of the 19th amendment. The first wave focused on suffrage or gaining the right to vote. In more recent times, second wave feminism is considered the 1960s through the late 1980s and third wave was 1990s through roughly 2008 (“The Women's Rights Movement”). These events shaped modern feminism because they inspired women in the second and third wave.

Targeted Issues in Society

One of the major factors in the separation of the second wave from the third wave is the problems faced by women in each time period. During the second wave, Many of Women’s economic problems come from discrimination in employment. Linda Tarr-Whelan suggests in her book, A Women's Rights Agenda for the States, that this discrimination was found in the form of attitudes and actions that stopped women from being hired, promoted, or paid adequately for their work. Many laws aimed to remove this discrimination such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Equal Pay Act of 1963, Executive order 11246, and the Equal Education amendments of 1972 (Tarr-Whelan 16). All of these laws focused on the differences in education, pay, and opportunity differences between the sexes; however, many did not have lasting effects.

Another key issue for second wave feminists was the pay gap. For full-time working women, the pay gap has been the same since at least 1930. It is disappointing, but not shocking, that this consistent pay gap was 60 cents for every one dollar a man makes (Tarr-Whelan 21). While the pay gap has gotten significantly smaller, it can still be seen today.

One of the final issues the second wave fought for was reproductive rights. On January 22, 1973, Roe vs Wade, a supreme court case, stated that the constitutional right to privacy included “...a Woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy” (Tarr-Whelan 103). Women of the era aimed to expand on their reproductive right, or at least keep their right to choose protected (Tarr-Whelan 104). This issue is one that has never really disappeared. It may have started in the second wave, but this fight rages on today as seen with recent events in Poland.

On the other hand, women in the third wave fought against underemployment. Underemployment is when skilled, competent individuals have a job that does not utilize the full extent of their abilities. Many brilliant women were stuck in secretarial jobs or similar positions that served men (Heywood 15). Many people believed that these jobs were “women’s work” and women struggled to enter fields dominated by men such as medicine or business.

The third wave women faced problems pertaining to image and politics. While many of these issues were private and personal, women pushed to make them be seen in a public light. Issues pertaining to the home, families, women’s body, love, and reproduction suddenly became a political battle instead of a personal fight. Carol Hanisch, a radical feminist, originally published an article in 1969 titled, “personal is political”. The term stuck and was used to describe women’s major battle in the third wave (Finlayson 102, 122).

Another issue was the media. Women struggled with stereotypical images of women either being too weak or too demanding. The goal was to redefine these images as powerful and with the help of movies such as Mulan, the Incredibles, and even Sesame Street, young girls were able to see women being strong (“The Third Wave of Feminism”). In Mulan, girls could see a young woman that they would still consider a “princess” defying the gender stereotype that a woman’s only purpose is to marry. In the Incredibles, Helen and Bob act as partners. They both take care of the kids and they both work while supporting one another. This would help reshape girls’ views that men dominate the relationship and enforce the idea that relationships should be partnerships.

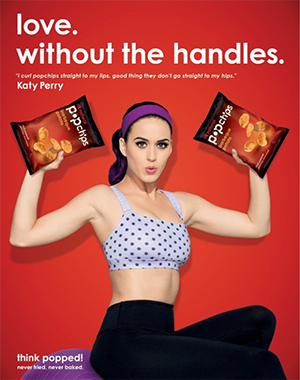

In the media, body image was also portrayed poorly. Advertising showed women unreasonably skinny and with flawless features. Advertising continues to objectify women by placing their worth in their appearance. Advertisements such as the shown in fig. 1  contributes to low self-esteem in girls that do not look like the ideal beauty standard (which most people do not). This ad shows Katy Perry as skinny, having perfectly toned muscles, and with beautiful facial features. Third wave advocates targeted unhealthy media like these advertisements. Such images discouraged women from participating in activities that would build any muscle or fat, whereas men were shown in strength building activities. Some feminists believe that “the superior physical strength of men and boys is at least partly a product of the differences in the ways in which boys and girls are encouraged to use their bodies” (Finlayson 38).

contributes to low self-esteem in girls that do not look like the ideal beauty standard (which most people do not). This ad shows Katy Perry as skinny, having perfectly toned muscles, and with beautiful facial features. Third wave advocates targeted unhealthy media like these advertisements. Such images discouraged women from participating in activities that would build any muscle or fat, whereas men were shown in strength building activities. Some feminists believe that “the superior physical strength of men and boys is at least partly a product of the differences in the ways in which boys and girls are encouraged to use their bodies” (Finlayson 38).

(Fig. 1. Katy Perry in an advertisement for Pop Chips. Online image. Brandingmag, 30 Aug. 2012, https://www.brandingmag.com/2012/08/30/katy-perry-popchips/. Web. 1 Nov. 2020.)

Goals of Each Wave

The goals of the second and third wave feminist movements also differed. While both aimed to eliminate the issues they faced, they had separate, more specific goals. Imelda Whelehan, a Women’s Studies professor at the De Montfort University, insists that activists in the second wave had a goal to challenge traditional definitions of what it means to be a woman (Whelehan 5). One way they challenged this definition was through political movements in the 1960s called the Women’s Rights Movement. During this time, professional women started to push the federal government with the goal of equal rights in the workplace in mind. While many women now had the opportunity to join the workforce, they still faced discrimination on a day-to-day basis by their male counterparts (Nicholson 2). As women started to spread out into new career paths, they looked for respect by their coworkers and more equal pay.

Another goal in the time period was to draw out women's feelings of dissatisfaction with their life as a housewife as they realized their potential in the workforce. This initiative was mostly aimed at middle-class women (Nicholson 9). Goals of the second wave were driving forces in women's daily life, especially at work.

The women in the third wave had a goal to focus on inclusion. The movement is now known for including more women of color than past waves (“The Third Wave of Feminism”). The third wave continued to fight for many of the same social issues as the second wave, yet they fought with a bigger front. There were people of all genders, sexualities, nationalities, and classes fighting for rights to equal pay, work, and access.

Young women also became much more important than in the past. Leslie Heywood and Jennifer Drake argue in their book, Third Wave Agenda: Being Feminist, Doing Feminism, that another goal of the third wave was to transform the culture of young women. During the second wave, Feminism was considered to be for “grown women,” but in the third wave this changed. Women wanted to change how young girls viewed themselves and help guide them to their rightful, powerful, place in society (Heywood and Drake 13). This idea was reinforced by the changing representation in movies and television as discussed earlier.

Views of oppression were changing; the goal was to reveal that everyone is oppressed in different ways. One definition of oppression does not hold true to everyone, and it is imperative that women recognize this so they can help people who are oppressed in ways different from themselves (Heywood and Drake 19). This new idea of oppression inspired a goal of the third wave, allowing individuality to be the motivating force in women’s lives. Since so many women were a part of the movement that hadn't been before, feminism needed to take on an individual meaning to each person in order to change society (Heywood and Drake 3). The goals of third wave feminists were different from second wave feminists because they focused included many more women than just middle-aged, middle-class, white women.

Significant People in the Movement

Prominent people contrast in these waves as well. In the second wave, Betty Friedan could be considered a leader in feminism. Friedan was born in 1921, a time where most women did not have jobs outside of the house. She graduated college as Valedictorian, but soon after she became a devoted housewife and mother. What led her to popular reputation was a study she did before her 15-year college reunion. She conducted a survey of her past classmates, specifically women, and asked them to self-report where they were at in life in terms of their goals. She found that she wasn’t alone in her feelings of unhappiness with her home life. The discoveries from this study led her to publish The Feminine Mystique in 1963. Manon Parry, a professor at the University of Amsterdam, claims in her American Journal of Public Health article that this book is arguably “[t]he founding text of modern feminism” (Parry). The book concluded that not all women find fulfillment in being a wife and a mother in replacement of a traditional career. Friedan explained in detail how the unequal opportunity and independence of women, when compared to that of men, was the cause of women's unhappiness. In 1996, Betty Friedan helped form NOW (National Organization of Women). She was the president of this organization until 1970. During this time, her most remembered contribution was organizing the Women’s Strike for Equality in Washington D.C. (Parry). Betty Friedan's impact in the second wave of feminism is undeniable, she was a spark that many women needed to get involved.

A woman named Rebecca Walker was another influential figure in the third wave. Walker was the daughter of a second wave activist named Alice Walker. In 1992 she founded the Third Wave Direct Action Corporation which later became the Third Wave Foundation. The aim of this project was to support people working for gender justice as well as other forms of justice. She was pushed to fame in 1992 when her article, “I am Third Wave,” was published in Ms. Magazine. Then, in 1994, Alice Walker was named as one of the 50 future leaders of America by Time (“The Third Wave of Feminism”). Having powerful role models such as Rebecca Walker was important during the third wave and allowed women to build off of one another.

Another impactful woman in the third wave is former First Lady, Michelle Obama. Michelle Obama is very passionate about her belief that girls can change the world if they are given proper education, and her husband’s presidency gave here the platform to advocate for that. Obama gave girls someone to look up to who had achieved high social status. She especially impacted young African American girls who do not see many people in the media who look like them. Obama gave a speech on International Women’s Day in 2016 to celebrate the one-year anniversary of her program, Let Girls Learn. She focused on the fact that “62 million girls worldwide…girls who are just as smart, and hardworking as we are…aren’t getting the opportunities that we sometimes take for granted” (PBS NewsHour). The former First Lady believes that, as women, we all have a moment of awakening. A time when we are “overlooked, underestimated, half listened to, or [someone] turns to a man for clarification” (PBS NewsHour). Obama has helped feminists recognize that education is a global problem that affects each of us personally. We need to keep fighting so that women can be represented on the level of law and politics (PBS NewsHour). It is clear that by changing our attitudes and beliefs, we can help all girls reach their full potential.

The Impact of Music

Along with people, popular music also played an influential role. In the second wave, musicians such as Aretha Franklin and Odetta Holmes used their platform to advocate for feminism. These women blended their political views with art to perform their pieces. Aretha Franklin is well known for “R-E-S-P-E-C-T,” which was released in 1967. This song resonated with many women of the generation, especially African Americans, and showed them that it is okay to ask for the respect they deserve. While Odetta wrote very few of her own songs, her powerful voice and the spin she took on each song turned everything she sang into a feminist anthem (Watson). Women have always been underrepresented in the music industry. So, not only did having these songs to listen to give adult women a sense of empowerment, it gave young girls someone to look up to and helped them believe they could do any job they wanted. These artists along with many more helped drive the second wave of feminism and foster the movement’s goals.

Music changed completely in the third wave. The major movement in women's music was called Riot Grrrl and can be simply put as punk rock feminism. In 1991, Riot Grrrl was started by a group of women in Washington D.C. who wanted to become more involved in the predominantly male scene of punk rock (“Signs”). When punk rock first began, it was rather supportive of the feminist ideals. However, once it became commercialized, the music fell into the mainstream system and was squashed under the foot of the patriarchy. The name “Riot Grrrl” can be attributed to Kathleen Hanna, a member of the band Bikini Kill. The name was meant to change the word girl into something more assertive, so they replaced “ir” to a growling sound “rrr”. Important artists in this movement include Bikini Kill and Bratmobile (“Signs”). Music, such as Riot Grrrl, inspired many feminists in the third wave.

Women are still fighting to make themselves more relevant in music today. Billboard statistics show that in the entire industry only 16.8% are women, this includes performers, songwriters, and producers (Pajer). Kerry Rork, a graduate student at Duke University studying history with an emphasis on social movements, published an article that talks about modern feminism in music. She further analyzed the fact that, unfortunately, even performers that we consider to be feminist role models have their lyrics written by men most of the time. Women musicians such as Lady Gaga, Billie Eilish, and Beyonce are starting to outwardly express when they face injustice in the industry and work to support other female artists. Lizzo fully embodies the feminist ideals as she promotes positive body image while singing songs many women think of as empowering (Rork).

Not only are women becoming more involved in the music industry, they are also spreading to new genres. Women are more prevalent in country and rap today than in the past. For the longest time men dominated rap and used lyrics that were demeaning and sexualized women. However, artists such as Cardi B., Nicki Minaj, and Megan Thee Stallion have become popular in the rap industry as they have given power back to women, allowing them to talk about their own bodies.

Movements and Protests

Large protests, with many people in attendance, defined the second wave of feminism. In 1968, demonstrations occurred at a Miss America contest in Atlantic City. Susan Brownmiller, author of Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape, explained they were protesting the idea that “[w]omen in our society are forced daily to compete for male approval, enslaved by ludicrous beauty standards that we ourselves are conditioned to take seriously and accept” (Whelehan 5). The protest was not violent but included a lot of extreme visuals. The protesters attempted to show spectators the connection between this event and the problems in society as a whole. The protesters encouraged other women to take part in the “Freedom Trash Bucket,” this was a large trash can set up for women to throw bras and girdles into. This event signaled a new era of direct action and focused on the goal of improving body image (Whelehan 6).

The Women’s Strike for Equality was held on August 26, 1970. It was sponsored by NOW, headed by Betty Friedan, and celebrated the 50th anniversary of the 19th amendment. The New York Times wrote an article the next day that asserted the goals of this strike including workplace equality, free abortion, and childcare. The strike took place in New York where 10,000 people gathered with posters and speeches. At the same time, many other protests were held across the country. With significant media coverage, this can be considered a spark for the second wave (Charlton).

Rather similarly, in the third wave many protests were held. In 1992, The March for Women’s Rights drew 500,000 people to the capital to advocate for abortion rights. In attendance were many congressional candidates and a few presidential candidates. This event was also planned by NOW and consisted of four hours of peaceful protesting. The cause of this protest was the Supreme Court being faced with a case that might put the decision from Roe vs Wade at risk. Roe vs Wade deemed abortion a constitutional right in the first trimester; a Pennsylvania law was challenging that and had made it all the way to the supreme court (Spolar). It is clear by the number of people present at these protests that women will stand up if they believe their rights have been violated.

In an article for the History channel, Sarah Pruitt insists that another significant event in the third wave was Anita Hill’s testimony. Anita Hill was an African American law professor who pursued the sexual harassment she had faced by Clarence Thomas, a supreme court nominee. She testified that he had repeatedly asked her out, and after her refusal he continued to harass her. All of which Thomas denied. It didn’t have the desired effect immediately since Thomas was still approved for the Supreme Court, but the impact on women and the feminist movement was remarkable. Sharing her experience encouraged other women who experienced the same thing that they need to speak out about it. Women began calling the National Women’s Law Center in tremendous numbers, asking what to do about the harassment they faced. This eventually led Congress to pass the civil rights act of 1991, which gave more legal help to victims of workplace harassment. The whole situation that Hill initiated led to 1992 being named “year of the women.” In 1992, more women were elected to office than ever before (Pruitt). The March for Women’s Lives and the Anita Hill testimony helped inspire many women in the third wave.

Accomplishments

When reflecting on their goals, it is clear that each of the waves accomplished very different things. The biggest accomplishment of the second wave was helping women realize that it was possible to be ambitious, and still be “feminine” (Heywood 11). Other evidence of the success of the second wave includes St. Paul opening the first shelter for battered wives in 1972. In that same year, Los Angeles opened the first gynecological clinic. These are both resources that help women with basic necessities. It is rather sad that we did not have resources like this before, but the second wave made them possible for all future generations.

Sexual harassment is less tolerated today and talked about more thanks to the feminist movement. As published in the textbook, Women's Movements: Organizing for Change, 88% of 9,000 women who replied to a Redbook Magazine survey (1996) which asked if the reader had received unwanted sexual attention at work said “Yes.” This was an accomplishment because sexual harassment had not been publicly discussed before the feminist movement (Gleb and Klein 12). Allowing for open communication about these difficult topics, makes it easier for people to become involved.

Finally, feminist movements that were organized in the 1970s raised questions about women's personal and political role in society. They challenged women to think about their daily roles and behaviors, sparking a re-evaluation of the role women play in families, workplaces, relationships, and as citizens (Gleb and Klein 26). In the second wave, many women improved their work and personal lives by accomplishing the goals of the movement.

The third wave accomplished many of their goals as well. As internet access became easier, blogs and e-magazines swelled. New technology made it easy to transmit information and messages to large audiences. This greatly helped people gain a better understanding of the feminist movement and spread the idea that anyone can be a “feminist” (“The Third Wave of Feminism”). The third wave was also able to transition away from the “victim feminism” of the second wave, and shift more towards “power feminism” allowing their movements to build off of those who came before them. The second wave is sometimes referred to as “victim feminism” because some of the activists promoted the idea that women were weak and needed protection. Their idea of feminism aimed to protect women rather than allowing women to take control of their own lives.

The third wave also achieved its goal of inclusion. The term “third wave” refers to a much more diverse group of activists than ever before (Heywood 1). Since the beginning of feminism, not much has been done to be inclusive of minorities. That started to change in the third wave with the introduction of the term “intersectionality”. This word started to appear all over in 1989 when it was first written by Kimberlé Crenshaw, a race theorist. It made feminism more inclusive by recognizing privilege and explaining that while the majority of women face the same injustices, it can be more extreme for certain groups of people because of the overlap of oppression. It started out just as racism and sexism overlapping but has spread to other forms of discrimination such as class and sexuality (“Guides: A Brief History of Civil Rights”). Overall, the third wave was very successful in meeting its goals, yet some people argue that enough was not done and we need a fourth wave of feminism.

Conclusion

In terms of recent feminism, the second and third wave are notably different in regard to the problems faced by women, the goals of the movement, occurrences during the movement, and the overall accomplishments of the two waves. While there are vast differences between these waves, they both are fighting on the front of feminism by advocating for equality of the sexes in all areas of life. Each wave has accomplished remarkable advances for women, yet there still continues to be new challenges to face. Recently, it is arguable that a fourth wave of feminism has begun. In most recent feminism, there is a focus on social media and rape culture. This is present in our daily lives with movements such as “TIME’S UP” and “Me Too”. Many social media apps are started to push away from only promoting “ideal” body types and many modern feminists push body positivity. With the death of such a powerful female role model such as Ruth Bader Ginsburg, we are surly going to need more women to step up and lead us in the continued pursuit of equality. In order to provide the optimum world for women, it is important to analyze how past waves have been successful, where they have failed, and how they compare to one another. By doing so we can work to end the challenges that women still face in today's world. Then, one day, “feminism” will not be limited in its reaches, instead everyone will recognize this term as a part of their lifestyle.

Works Cited

“A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States: Feminism and Intersectionality.” Guides, Georgetown Law Library, 29 July 2020, guides.ll.georgetown.edu/c.php?g=592919&p=4172371.

Charlton, Linda. “Women March Down Fifth in Equality Drive.” The New York Times, The New York Times Archives, 27 Aug. 1970, www.nytimes.com/1970/08/27/archives/women-march-down-fifth-in-equality-…;

Finlayson, Lorna. An Introduction to Feminism. Cambridge U P, 2017.

Gelb, Joyce, and Ethel Klein. Women's Movements: Organizing for Change. American Political Science Association, 1988.

Heywood, Leslie, and Jennifer Drake. Third Wave Agenda: Being Feminist, Doing Feminism. U of Minnesota P, 2003.

Nicholson, Linda J. The Second Wave Feminism Reader: A Reader in Feminist Theory. Routledge, 1997.

Pajer, Nicole. “New Report Shows Major Lack of Representation by Women in the Music Industry.” Billboard, 26 Jan. 2018, www.billboard.com/articles/news/8096196/new-report-shows-major-lack-rep….

Parry, Manon. “Betty Friedan: Feminist Icon and Founder of the National Organization For Women. 2006.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 100, no. 9, American Public Health Association, Sept. 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2920964/.

PBS NewsHour. “Watch Michelle Obama speak on International Women's Day.” Online video clip. YouTube, 8 Mar. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FIN1F0TyadM.

Pruitt, Sarah. “How Anita Hill's Testimony Made America Cringe-And Change.” History, A&E Television Networks, 26 Sept. 2018, www.history.com/news/anita-hill-confirmation-hearings-impact.

Rork, Kerry. “It's Time for the Music Industry to Have a Feminist Revolution.” The Chronicle, 24 Oct. 2019, www.dukechronicle.com/article/2019/10/its-time-for-the-music-industry-t…;

Rosenberg, Jessica, et al. “Riot Grrrl: Revolutions from Within.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, (n.d), www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/495289.

Spolar, Christine. “Abotion-Rights Rally Draws Half a Million Marchers.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 6 Apr. 1992, www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1992/04/06/abortion-rights-rall….

Tarr-Whelan, Linda. A Women's Rights Agenda for the States. Conference on Alternative State and Local Policies, 1984.

“The Third Wave of Feminism.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., (n.d), www.britannica.com/topic/feminism/The-third-wave-of-feminism.

Watson, Elwood. “Perspective : Aretha Franklin, Feminist and Activist.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 1 Apr. 2019, www.washingtonpost.com/news/made-by-history/wp/2018/08/19/aretha-frankl….

Whelehan, Imelda. Modern Feminist Thought from the Second Wave to "Post-Feminism." Rawat Publications, 2015.

“Women's Liberation Movement Print Culture.” Duke Digital Collections, (n.d), repository.duke.edu/dc/wlmpc.

“The Women's Rights Movement, 1848–1920: US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives.” The Women's Rights Movement, 1848-1920, US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives, (n.d), history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/WIC/Historical-Essays/No-Lady/Womens-Rights/.