by Bobbi Jo Reinking

During the 1970s, North Hennepin Community College formed an education program designed specifically for the elderly, which had never been done before. I wanted to find out why this program was so important, how it changed North Hennepin Community College and the surrounding community. It had significant effects upon the school itself, ranging from bringing elderly students and young students together, to having the program featured in TIME magazine and recognized by the state and other institutions nationwide, to allowing elderly citizens expand their minds by supplying them with a vast and valuable knowledge on many different subjects.

Overall, I found that the Seniors on Campus Program was beneficial in a number of ways; however, the most important proved to be how it affected the sense of community within the school. These effects correlated with North Hennepin’s transformation from a junior college into a community college. I strongly believe that the Seniors on Campus Program helped emphasize and initiate the theme of community itself within the school as well as throughout the surrounding area.

Before we start talking about the specific effects that this program had upon North Hennepin Community College and the community, we should first discuss how the program first began and how it developed. It started back in the fall of 1970. Late one evening, a van illegally drove down the sidewalk that intersects the inside courtyard at NHCC. The van pulled up to a building where a meeting was being held on housing and care for the elderly. However, all the attendees were younger professionals. Out from the van came fifteen senior citizens from the United Seniors of Minneapolis. They wanted to know why they had not been invited to participate in the seminar, and they demanded that they be admitted (even though they had not registered for the seminar) so that they could share their views openly.

Bruce Bauer, North Hennepin’s director of community services, first acted defensively, but then rethought his opinion. He recognized that many colleges around the nation were not doing nearly enough for the elderly. Bauer then helped the activists form a Senior Advisory Committee at the school and even advised them on the planning of the new senior education program itself (Sugnet 1976).

On Monday, July 12, 1971 nearly 400 senior citizens entered the campus in what they called a “campus invasion.” Bruce Bauer stated that “the idea of senior adults attending classes and designing programs to meet their specific educational needs and interests has wide interest and support in the total North Hennepin area” (Senior Adults 1971). With the theme of “Invading the Campus,” the program helped the senior citizens get to know the facilities and programs of the college, as well as help give input for future programs that are designed specifically for the elderly (College to Host 1971).

According to a newspaper article from the North Hennepin Post in their “Over ’60’ section, Bauer states that, “his staff is reviewing surveys that senior citizens completed at their open house last week, and an amazing list for seniors is also being established” (Over ’60’ 1971). Right from the start, the program had renowned positive effects. Senior citizens in the surrounding North Hennepin area could now gain an education for free. They were also already getting involved in student life through the Senior Advisory Committee and participating in these “Campus Invasions.”

The following year on October 5, 1972 a second “Campus Invasion” was set up with the theme “A Healthy Day” (Senior Citizens 1972). Seniors took tests for breathing and diabetes, and picked up information on social security and housing. They were also able to register for free classes. According to Bruce Bauer “They choose the courses and instructors” (Campus Invaded 1972).

On September 19th, 1973 they again hosted a campus invasion, revisiting the theme of “Have a Healthy Day,” where guests were invited to participate in free eye, ear, heart disease and diabetes tests. There was also a film shown providing information on Glaucoma (a disease of the eye). As before, seniors were allowed to register for classes from free or very little tuition (Campus Invasion planned 1973). Some of these classes included a general equivalency diploma for those who had not finished high school as well as other courses like painting, psychology, budgeting, choir, public speaking and many more. (Parsons 1972).

Over time the Seniors on Campus program became an essential component to not only North Hennepin, but the surrounding community. In an article from the Brooklyn Center-Brooklyn Park Sun, Irene Parsons stated that, “this educational service to the elderly is one of the few offered any place in the nation, and it already has had an impact on the lives of senior students” (Parsons 1972).

This program gave seniors a unique opportunity. A senior student, Simon Halls, stated that he took public speaking classes hoping that it would help him be a more effective president of United Senior, an elderly organization from area suburbs. Another student, Ollie Paquette, was less interested in the “intellectual life,” but more concerned with senior citizen housing and social life. He even put together the Anoka senior citizen group and continued his presidency for three consecutive years (Parsons 1972).

These classes were not just helping these senior students expand their general knowledge, North Hennepin was also helping them succeed in their everyday lives, which really supports the emphasis of the new sense of community that was building at the school. Doctor Helling stated himself in a newspaper editorial that “North Hennepin is a community institution. It is in and of the community. It is most appropriately called a community college” (Helling 1968).

In addition to enriching the everyday lives of the elderly, the senior citizen education program also coincided with North Hennepin Junior College’s transformation into North Hennepin Community College. A junior college typically only has one purpose, and that is to prepare students to transfer to a four-year university.

On the other hand, community colleges serve the public as a whole. They not only help prep students for the university level, but they also provide workforce development, skills training, various noncredit programs, community enrichment programs and even cultural activities. Connor Welsh states in his essay, “Transformation from a Junior College into a Community College,” that “the college felt that the label ‘Community College’ reflected their true mission” (Welsh 2012, 4).

Being a community college would erase the negative association that comes with being a junior college; instead the school wanted to be a place that the community could utilize. It would also be seen as a more legitimate institution. Doctor Helling advocated this change from the very beginning of his hire in 1967. He wanted to make North Hennepin into a place that served the public on various levels and formats. To do this, he wanted to change the demographic of the institution so it could be more accessible.

Welsh states that, “the college wanted to be seen as a program where members of the community could come together and further their own education” (Welsh 2012, 5). This is one of the reasons why the Seniors on Campus program was initially put together and how it gained momentum. Both the seniors program and the name change indicate the strong desire for community that existed at the college in its early years.

Once the school had made its transition and the senior program had been established, the school started to truly become a community. The new education program brought senior citizens onto a campus that was, for the most part, predominantly filled with younger college-aged students. Some thought that this would bring on problems between the two age groups, but instead the program helped to fill in the generation gap, associating each generation of students more effectively with one another.

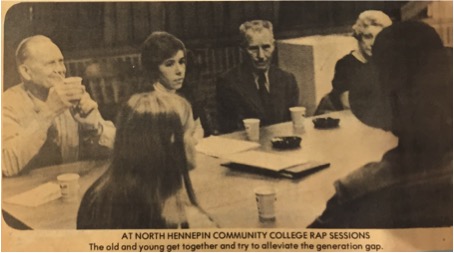

One compelling example of this comes from an article from the Brooklyn Park Post from 1974. Doug Germundsen describes how North Hennepin helped bridge the gap between the two generations by offering non-credit “rap sessions.” The class actually was offered to the entire community, anyone could come in and “rap.” The course did not have tests, grades, or rules. It allowed for a neutral meeting ground for the young, the middle aged, and the elderly. Kathy McLearen (the program assistant for senior citizens on campus), stated that: “This is the third year we’ve offered sessions, I guess it just grew out of the curiosity that grew from having seniors and young students enrolled on the same campus. There are quite a few seniors enrolled here at the community college, and you know, it just seemed like a good idea to get them together with the younger students” (Germundsen 1974). At these “rap sessions,” discussion would flow freely and the subjects debated included: evolution, vocationalism vs college education, problems parents had explaining sex to their children, and the Vietnam War. Karl Munson, a senior citizen from Brooklyn Park, said that the sessions were truly beneficial for both the youth and the seniors who attended. He stated that “we get along great with these kids, anyone interested should come on over and try it out” (Germundsen 1974). Harriet Heesen also admitted that after taking part in the rap sessions with the students, she was “quite shocked sometimes,” and also stated that “maybe we don’t have as big a gap as I’d thought” (Germundsen 1974).

The sessions were very welcoming. Literally anyone could attend, state their own opinions on various topics, and listen to other’s opinions (North Hennepin Works 1974). The following photo is from an issue of the Brooklyn Park Post in 1974. It shows one of the many rap sessions (North Hennepin Works 1974).

Courtesy of the Brooklyn Park Post

While rap sessions contributed the most to closing the generation gap between the elderly and the young, there were other factors that helped. In 1972, Dan Sundquist and his wife Loretta put themselves in a two-year program at NHCC based on recreation leadership to help them organize recreational programs for mobile home parks and dude ranches in Minnesota and in Arizona. While Sundquist knew he would be working with other senior citizens most of the time, he also recognized the younger student demographic at North Hennepin. He bridged the gap between young and old by running for a seat on the student council. He said, “I was asked to run and thought I’d be too conservative. But then I thought, ‘what the heck!’” He was indeed elected and was even given the nickname “Sugar Dan” (Parsons 1972).

Having young students and senior students interact together was highly beneficial because it brought the two generations together in a new, positive way. They could now relate to each other on a much higher level than ever before; they bonded together not only on an intellectual level but also on a social level. This also tied back into this new sense of community at NHCC.

The word community is defined as a “feeling of fellowship with others, as a result of sharing common attitudes, interests, and goals.” North Hennepin was bringing the surrounding peoples into their school and as a result was becoming its own unique community.

The Seniors on Campus Program also acquired some national attention. Charles J. Sugnet says in his journal article “Senior Power at North Hennepin”: “Articles had appeared in newspapers and professional journals and the college had received over 150 requests for information from places as diverse as Boston University and Bay De Noc Community College is Escanaba, Michigan. The program had been referred to as one of several models in Never Too Old to Learn, published by the Academy for Educational Development, and in Older Americans and Community Colleges: A Guide for Program Implementation…” (Sugnet 1976, 64).

North Hennepin Community College was also featured in TIME magazine in the July 17, 1972 issue. The article describes how the program started and some of the classes that were featured. It also mentioned how the program influenced other schools to start their own senior education programs. TIME remarks that at Stanford, a professor had started planning an “emeritus university,” a university for retired people.

The article also states that programs for senior citizens were already being formed at colleges in St. Petersburg, Milwaukee, and Sacramento. One had already opened and registered 200 seniors at Mercyhurst College in Erie Pennsylvania (Learning for the Aged 1972, 48).

Sugnet explains in his article “Senior Power at North Hennepin” that enrollments were actually down in 1976 at North Hennepin from what they were in 1973-1974, namely due to the fact that many other schools and institutions had followed North Hennepin’s lead and started developing their very own senior programs (Sugnet 1976, 64). This could be the reason why the program ended or regressed.

There was also the fact that in 1977, Bruce Bauer, who was the main advocate for the program, had moved on to become president of Itasca Community College in Grand Rapids. There is not much information on him at Itasca Community College because of his untimely death in 1977. The local YMCA in Grand Rapids has a Bruce Bauer Senior Center. Itasca Community College has a Bruce Bauer Award, a scholarship for students who have superb leadership, scholarship and citizenship skills.

Bruce Bauer was the primary supporter for the senior program at North Hennepin and his transfer to Itasca Community College could be the reason why the program began to fade away in the late seventies. Another possible explanation for the program’s recession could be that North Hennepin may have lost its federal grant under Title III of the Older Americans Act of 1965. Unfortunately, I could not find any evidence to confirm this theory.

From my research I have concluded that the Seniors on Campus Program acted as a way to bring the surrounding community and school together in multiple ways. The program helped educate the elderly and proved to the nation that one is never too old to gain an education.

Overall, the senior program showed that age diversity within a college institution can benefit a school in endless ways. The program brought senior citizens into North Hennepin, making it more accessible for them to participate with the rest of the community, and vice versa. It allowed young and old alike to connect both intellectually and socially. The senior students became an integral part of North Hennepin, which helped establish and emphasize the sense of community at the school.

Appendix

1970: Fifteen seniors citizens interrupt meeting being held at North Hennepin demanding that they be admitted and be allowed to state their opinions on senior care and housing.

1971: First senior “Campus Invasion” takes place at North Hennepin. Hundreds of elders come to school and register for free classes for the first time.

1971: North Hennepin Junior College officially changes its name to North Hennepin Community College.

1972: Second “Campus Invasion” takes place at NHCC. Free health checks were available, and registration for free classes as well.

1972: Dan Sundquist bridges the age gap by running for student council member, he is elected and is given the nickname “Sugar Dan.”

1972: North Hennepin’s Seniors on Campus Program is featured in TIME Magazine in its July 17, 1972 issue.

1973: Third “Campus Invasion” takes place at North Hennepin. Like before, free health checks were available as well as registration for free classes.

1974: “Rap” sessions begin to take place to help bridge the gap between the young students and the senior students.

1977: Bruce Bauer leaves North Hennepin to become president of Itasca Community College

Reference List

Primary

“Campus Invaded by Hundreds of Elders.” Brooklyn Park-Brooklyn Center Sun, October 11, 1972.

“Campus Invasion Planned for Sept. 19.” North Hennepin Post, August 29, 1973.

“College to Host Senior Citizens.” Brooklyn Park/Brooklyn Center Post, July 22, 1971.

Germundsen, Doug. “North Hennepin Works on Generation Gap.” Brooklyn Park Post, November 7, 1974.

Helling, John. 1968. “Junior College? President Says Community College More Appropriate.” North Hennepin Post, August 22.

“Learning for the Aged.” TIME Magazine, July 17, 1972, 48.

“Over ’60’ … Plus a College Visit at North Hennepin.” North Hennepin Post, July 22, 1971.

Parsons, Irene. “Senior’s Powerful Force at North Hennepin.” The Brooklyn Center-Brooklyn Park Sun, August 2, 1972.

“Senior Adults to ‘Invade Campus’ Of North Hennepin Junior College.” Brooklyn Park Post, July 7, 1971.

“Senior Citizens to Invade Jr. College.” North Hennepin Post, September 28, 1972.

Secondary

Sugnet, Charles. “Community Colleges: Senior Power at North Hennepin.” Change 8, no. 4 (1976): 51,64. Accessed November 8, 2015. http://www.jstor.org.

Welsh, Connor. “Transformation from a Junior College into a Community College.” 2012.